I descended down a sheer granite wall, following a narrow, but ever widening crack. The crack was full of life and the critters I discovered became increasing larger as I neared the bottom. At the widest point I flashed my light back into the darkness, and one of the most hideous faces in the ocean stared back at me, a wolf-eel. I’m not sure which one of us was more startled. Wolf-eels are a particularly shy fish and spend most of the day back in their dens unseen. They are also one of the most misunderstood California fish, and even though they may look like an eel, they are not.

Wolf-eels belong to the order Perciformes, the perch-like fish and the family Anarhichadidae, the wolffishes. This family has five species in two genera. The scientific name for our California wolf-eel is Anarrhichthys ocellatus, which is Latin for “fish with eye-like spots.” Although they superficially resemble moray eels they are not at all related. Moray eels belong to the order Anguilliformes, the true eels and the family Muraenidae, the moray eels. Wolf-eels are more closely related to our surfperches and fresh water perches than true eels, and should more precisely be called wolffishes.

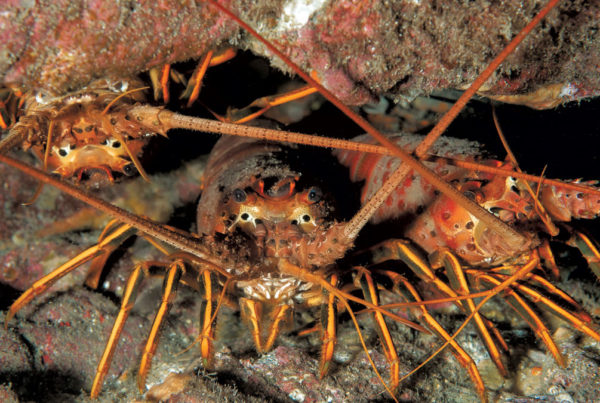

The California wolf-eels can grow to be up to eight feet long and is the longest member of their family. They are mostly shades of gray, but some are brownish. Juveniles may take on an orange-red hue. All have dark-centered eye-like spots along their bodies. Wolf-eels have a large, bulbous head. Mature males can be distinguished from females by their flabby, lumpy heads.

They may be found from the Sea of Japan to the Aleutian Islands to Southern California. Although, wolf-eels are most reliably found at many dive sites in British Columbia, they tend to move around somewhat, and in California there is no guaranteed place to spot them. There is a large population at North Farallon Island, and they are sometimes seen at the Barge, and at Eric’s Pinnacle in Monterey. They are occasionally found at the more northern of the Channel Islands—Santa Rosa and San Miguel.

Wolf-eels spend much of the day in their dens and are mostly overlooked by divers, although sometimes they may “porch sit.” At night they become active and leave their dens to hunt. They are egg layers and will line the back of their dens with a large gelatinous egg mass, and both the male and female will guard the nest until their young hatch. It is thought that wolf-eels mate for life.

These are not particularly handsome fish and have strong jaws with very strong conical canines and molars. These are needed to break up their favorite food—crustaceans, urchins, mussels, clams, and other hard-shelled invertebrates, as well as some fish. They have been observed killing and consuming lingcod of roughly the same size. They are rarely caught by hook and line fishermen, but will thrash violently when landed, and have been reported to bite a broomstick in half.

Wolf-eels are generally quite shy and will recede from divers if given the chance. One sure way to get a good look and maybe a photograph is to offer them a little treat. Offers of broken sea urchins are generally enthusiastically accepted, and you may gain a friend for life. Some divers take down packages of frozen anchovies, and these are rarely turned downed by hungry wolf-eels. If you choose to feed wolf-eels, remember to keep your fingers clear; they do have a very strong bite. They do, however, have distinctive personalities and make fascinating photographic subjects.