Strange things happen in Northern California during springtime. Campgrounds and motels that were unoccupied most of the winter are now sold out. Coastal roads that were once empty are bustling with traffic. Large numbers of employees are mysteriously absent from their jobs. A case for the X-Files? No, it’s simply the beginning of abalone season.

The red abalone is the world’s largest, and this mollusk thrives on Northern California’s inshore reefs. Red abalones are not as abundant as they once were, but with a little bit of knowledge, they are easy to harvest and make a mighty fine meal. We California divers are so fortunate to have one of the ocean’s tastiest treats in our local waters.

The abalone may be thought of as a cross between a squid and a scallop. It has the delicate flavor similar to a scallop, but, like squid, can toughen if overcooked and usually need to be pounded. When properly prepared, abalone is delicious. There is limited aquaculture for abalone and no commercial fishery in California. Generally speaking, if you want abalone, you must dive for it.

Abalone Basics

Abalones are mollusks‚non-segmented invertebrates with a mantle, gills, a rasping tongue, and a muscular foot. Abalones are further classified into the class called gastropods, which includes, snails, slugs, and nudibranchs. Gastropods are the most successful class of mollusks and over 35,000 living species are documented. Abalones and snails possess a single shell, which distinguishes them from other mollusks that have multiple component shells (chitons), two shells (clams, scallops and oysters), or no shells (octopus and squid). The most distinct feature of the gastropods is they all undergo a process called torsion. During development, their body twists around 180 degrees counter-clockwise such that their anus moves into a position directly over their head. Abalones are considered primitive animals, even for invertebrates, because they defecate on their own head. Apparently it was a major step in evolution to separate the input from the output.

As you clean your abalone it is easy to imagine why they are called gastropods, meaning, “stomach footed.” Most of the animal’s weight within the shell is its large, mushroom-shaped, muscular foot. It allows the abalone to crawl about, sometimes at an astonishing speed (well, for a snail), and it also creates a vacuum, like a suction cup, that holds the abalone to its rock. However, the large gland surrounding the foot is not its stomach, it is the reproductive gland. To be technically correct, they should have been named “reproductive gland footed” instead of “stomach footed.” There are male and female abalones. The males have cream-colored glands, and the females are green or blue-green.

All abalones are grouped into the family Haliotidae, in which there is one genus Haliotis. “Haliotis” translates into “sea ear,” which accurately describes the shape of the shell. Abalones also have conspicuous holes in their shells that are used to circulate water to extract oxygen, expel waste products, and spawn. There are eight abalone species in California’s waters: black, flat, green, pink, pinto, red, threaded, and white abalone, but the red abalone, Haliotis rufescens, is the only species that may be legally taken in California waters. The red abalone is the word’s largest. John Pepper holds the world record with a 12 and 5/16-inch monster.

Abalone Diving

Abalone may be found throughout the State, but may only be legally taken from the southern tip of Marin County north to the Oregon Boarder. Depending on your skill level, every cove, beach and rocky point is a potential dive site, however some areas are now closed due to the enactment of the Department of Fish and Wildlife Marine Conservation Areas.

Sonoma and Mendocino Counties represent a sweet spot for California abalone hunters. The visibility is generally a great deal better than points a bit north and south, and there are huge beds of giant kelp and bull kelp to keep the abalone well fed. There are also a large number of public entries to accommodate divers of all skill levels, and plenty of spots to launch boats and kayaks.

If you can dive to 30 feet, it’s likely you will get your limit of abalone at any entry on the North Coast. If you can only dive to 10 or 15 feet, you will have to select your sites more carefully. In the early days of the season many abalone may be found in shallow water right off the area’s most popular beaches. Later in the season, you will have to swim, hike, paddle, or motor a bit further to find plentiful abalone in shallow water. Detailed descriptions of popular dive sites may be found in past issues of California Diving News (www.cadivingnews.com), and nearly all the public accessible sites in the book, California Abalone Diving (by the author, available at local dive centers.).

Hunting Tips

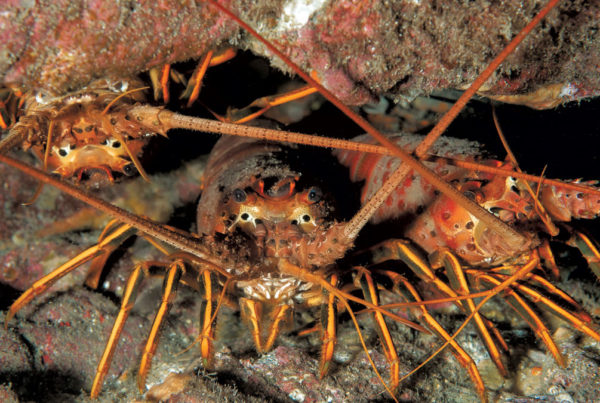

Abalones are always found attached to rocks, never on sand. Look at the base of rocks at the edge of sand channels or in cracks. Often abalones are found upside down, wedged in cracks. Sometimes, particularly late in the season you will encounter thick surface kelp and/or a layer of palm kelp that hovers a few feet off the bottom. You must swim through the layer of kelp to get to the abalones below.

Identifying an abalone can be difficult, especially for beginners. You will generally not find the rocks covered with polished, red shells. The shells tend to be covered with the same encrusting invertebrates and plants that are on the rocks they are sitting on. They can be well camouflaged. You can sometimes find an abalone by looking for an abalone-shaped bump on a rock. Most frequently I notice an abalone by the jet-black foot that stands out against the red or pink encrusting marine life. Often the newly formed edge of the shell has yet to acquire a covering of marine critters, and the shiny edge may catch your eye. You have to train yourself to distinguish your prey from the bottom. If you are having a hard time, try doing a “recon” scuba dive or diving in a reserve‚where there are plenty of abalone in plain sight‚just to learn what to look for.

Once you spot your abalone, make an estimate of its size and reject ones that are less than 7 inches. Some dive with a gauge, but most have marked their abalone iron with a scratch or wrap of waterproof tape at 7 inches. Don’t touch the abalone at this point or it will suck down and you will never get it off the rock. Sometimes it is impossible to accurately gauge an abalone that is way back in a crack. Judge its size as best you can, or hunt for one that looks “really big” if you cannot measure it before you pop it.

Try grabbing a piece of kelp and calming yourself while you consider how to pluck your abalone. This allows you to hold your breath longer, and gives you more time to select the optimal angle of attack with your abalone iron. In one swift motion slide your abalone iron between the abalone’s foot and its rock, and pop the abalone off by pulling your abalone iron away from the rock. Remember, you are not prying the abalone off; you are simply breaking the suction that holds it to the rock.

Once on the surface carefully measure your catch. A legal abalone will not fit through your gauge in the longest dimension. Always replace “short” abalone exactly where you found it, and hold it onto the rock until it sucks down. An abalone thrown overboard will sit on the bottom, shell down, and die. They cannot turn themselves over.

Abalone diving is a fun and rewarding way to enjoy Northern California sites. Just remember, dive within your own physical limits and observe all legal catch limits, too.

Abalone Diving Regs

Diving for abalone is governed by the most complex set of rules of any fishery. These rules are designed to limit the catch to preserve the fishery, and to thwart poachers. There was a significant change in the rules beginning in 2014. This included a later start time, the closure of the Fort Ross area, a lower annual take, and restricted limits on the abalone taken from Marin and Sonoma Counties.

The penalties for breaking these laws can be stiff, including hefty fines and confiscation of dive gear and vehicles. The most common offences are for blatant poaching. However, divers can get fined for helping another diver catch his abalone, undersized abalone, and report card violations.

Here is a subset of current regulations. The complete rules may be found at www.dfg.ca.gov.

Where: Abalone may only be taken north of the mouth of San Francisco Bay. Starting in 2014 the Fort Ross area has been closed indefinitely to abalone hunting. Abalone may not be taken in the many California Marine Protected Areas.

When: From 8 AM to one-half hour after sunset during the months of April through June, and August through November.

How Many: The possession and daily bag limit is 3. Each year only 18 abalones may be taken, and only 9 of these may be landed in Marin and Sonoma Counties.

Size: All landed abalones must be at least 7 inches in the longest dimension. All legal-sized abalone detached must be retained; you must stop after your limit is reached.

Gear: Divers must possess a legal abalone iron and measuring device. They must also have a fishing license and abalone report card and tags. The landed abalone must be tagged and the report card completed immediately after the abalones are landed on boat or shore. Only free divers and shore pickers may take abalone; no scuba is permitted.

Abalone Possession and Transportation: Abalones shall not be removed from their shell, except when being prepared for immediate consumption. Individuals taking abalone shall maintain separate possession of their abalone.

Safety First

Each year several abalone divers die in pursuit of their catch. The 2013 season was particularly tragic when three abalone hunters died in a single weekend in unrelated events.

Most of these incidents occur when hunters dive in conditions that are beyond their skill level. Divers should monitor sea conditions before starting their trip. NOAA has very accurate marine weather predictions and near real-time buoy information at www.wrh.noaa.gov/mtr/. Another good tool is managed by Scripps Institute of Oceanography at www.cdip.ucsd.edu/?nav=recent&sub=forecast.

Diving should be fantastic when the predicted wind is less than 10 knots, seas are less than 6 feet, and about 10 seconds apart. I suggest staying stay home anytime the winds are over 20 knots and seas over 9 feet.

Once on the beach, try observing the ocean for a good 20 minutes or more before committing to the dive. This will give you plenty of time to evaluate the sea conditions.

Make sure you are comfortable diving in kelp, including how to bend/snap it. Should you become entangled, simply pause and systematically remove the offending pieces, or get your buddy to help. Do not spin around looking for the kelp that is holding you; think of a fork in spaghetti. It is a good idea to “kelp proof” your gear. Tape the ends of your fin straps down with electrical tape. Don’t dive with unnecessary gear, and never abalone dive with a “clip” on your weight belt.

Speaking of weight belts, the vast majority of victims are recovered with their weight belts on. Try practicing dropping your belt, and realize your life is more valuable than the cost of a new belt.