Underwater photography involves a lot more than just making a dive and tripping the shutter. In last month’s issue I delved into the things you need to do before you dive to be sure your camera system is set up properly and functions as you expect it to. This month I am going to discuss some best practices for dealing with your digital images after your dives so you can find them, avoid losing them, and manipulate them so that your photographs look the way you want them to.

Avoiding Disorientation and Death

As an underwater photographer, if there is anything that will drive you absolutely mad it is not being able to find a particular photograph in your image library. You have a great shot. You know it is on your computer or an external hard drive somewhere, but for the life of you, you can’t figure out where somewhere is.

Here is a far worse scenario. Imagine storing your entire library of underwater images on a single hard drive and having that hard drive fail. Perhaps, by spending several thousand dollars you can have the image files saved. Perhaps, after spending several thousand dollars you’ll be told nothing could be done to retrieve those files.

These are, indeed, two nightmare scenarios that all photographers need to be cognizant of in the digital era. The good news is that both of these scenarios are preventable. If you do things the right way, finding and backing up images can be a snap. So, let’s get into the things you want to do to make sure you don’t learn hard lessons the hard way.

It makes perfect sense that the first thing we want to do after a dive is download images onto our computer and start to manipulate them with post-capture software such as Photoshop, Photoshop Elements, Lightroom, or Aperture. But for safety’s sake it makes much better sense to back-up image files before you do anything else. A lot of professional shooters back images up onto two separate hard drives so they have three verified copies of their images before they begin to view, edit and manipulate image files, and before they re-format their media card. Some people think two back-up copies is overkill, but redundancy goes a long way toward preventing disaster. Many pros keep an additional copy at a separate physical location to protect them from losing their library in the event of a fire, flood or other disaster.

Remember, there are two kinds of hard drives, those that have died, and those that are going to. The obvious takeaway message is to download and back-up your images onto another hard drive. Or two.

Delete, Delete, Delete

While there is not a single right way to deal with your images in the post-capture phase of your workflow, editing images is a logical next step. Start by deleting all of the shots that you absolutely know will never have a useful purpose. Getting rid of the “garbage” makes the rest of your process easier and faster.

My personal method is to import my images into Lightroom, a digital asset manger (DAM) software program made by Adobe. I edit my images from within Lightroom. You don’t have to use Lightroom, but it certainly is a powerful program as is Apple’s Aperture among others.

Keywording Is Key

In the digital era the use of keywords is the key to finding images in a timely manner. Keywords are words you add to the metadata of an image file to make images easy to find. They are the words you enter in “search boxes” when using online browsers to locate information about a given topic.

The use of keywords means you won’t have to remember when or where you took every picture of every subject in your image library, and then look in folders for every trip you have made to each destination to locate the desired images. Instead, you use keywords that you attach to image files to “call up” those images on your computer. That’s a beautiful thing!

The best time to add keywords is immediately after your initial edit before you start manipulating images. If you keyword before you manipulate images the keywords will be attached to every version of your images as you go forward. This means you won’t have to manually add the same keywords to different versions of the same image. Clearly, keywording images on the front end is a huge time saver that makes all versions of an image easier to find.

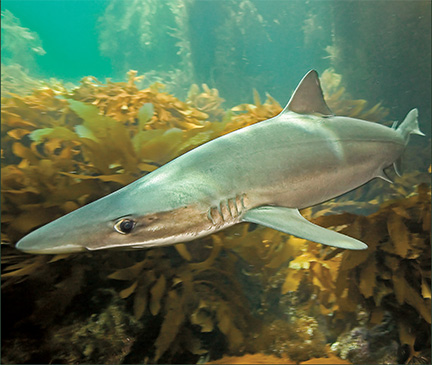

A number of software applications allow users to add keywords. You can add as few or as many keywords to a single image file as makes sense. The keywords I have attached for the accompanying image of a soupfin shark include “soupfin, shark, kelp, California, San Clemente Island and predator.” I can quickly find this image by conducting a search of the 100,000 plus images in my photo library with any of these keywords.

Developing A File Naming System

In addition to keywording it is very helpful to develop a folder and file naming system. The files produced by cameras are usually named with some sequence of letters and numbers that don’t mean anything in terms of what the picture is all about or when it was created. For example, the name of a file produced by one of my cameras is _MS20056.NEF. However, file names can be very helpful in identifying and locating an image.

The best practices guide for digital photography suggest re-naming image files in the following manner: For a given trip or day of diving, create a master folder that is named according to the first day of the trip and the location or subject. Every time you download a card of images create a sub-folder that is named according to the date, subject and download number for that day. For example, on a trip I made that began on August 16, 2007 I named my master folder 20070816_Catalina Island. The first sub-folder of downloaded images is named 20070816_giant sea bass_01, and the first two images in that folder have been re-named 20070816_giantsbass_01.001.NEF and 20100816_giantsbass_01.002.NEF. When renaming, my software automatically applies the last three numbers.

Image manipulation software programs allow you to rename files in batches, a task that can be performed in a matter of seconds.

The reason I begin the names of my image files with the year, month and date is that computers are made to “think” in chronological order, and if I ever lose a file I can locate it via the “find” function on my computer by typing in the date or part of the date when an image was acquired. Only using a destination or subject name can work, but you need to be consistent when you assign names. You don’t want to name one folder “Point Lobos” and another “Dives with Chris” because you might have to remember those exact names at a later time to locate those folders unless you have also keyworded your images.

Calibrate and Profile Your Monitor

Have you ever looked at a picture on your computer screen, and altered it with your software so the image looked stunning, only to take the image file to a printer and have the colors in the final print look awful? There is a natural tendency to blame the printing facility, but the odds are the fault lies with not calibrating and profiling your computer monitor.

The acts of calibrating, profiling and selecting a color space (see last month’s issue of CDN) enable you to provide images to a printer or show them on a projector in a form that the printer or projector should be able to accurately reproduce. Calibrating and profiling are the foundations of your photographic house.

Calibrating your monitor means using known standards such as a color chart and using specialized hardware and software to apply those standards to adjust and set color parameters on your computer. Profiling means taking the known state to the conditions you are working under. Consider that the same picture will look significantly different when viewed on a computer monitor in a brightly lit room and a dark room. Same image, different looks. Calibrating and profiling eliminate this problem and provide accuracy and consistency.

Pros check the calibration of their monitor about once a month, but profile their monitor every time they use it to manipulate images.

Tweaking and Trimming

At the very least, you will probably want to be able to perform basic post-capture image manipulation on your computer. You don’t need to become a Photoshop guru, but you will want to acquire some kind of image manipulation software and learn some basics so you can crop images and remove backscatter, etc. We’ll address these topics in a future article. You can likely find classes available at computer specialty stores or at your local community college.

Most photographers don’t manipulate an image until they have specific use for it such as showing the image in a slide show. At that time they “tweak” the image and save a copy of that image that matches the needed usage in terms of size, the sharpening required, and color space.

Clearly, there is a lot more to underwater photography than just going diving and taking pictures. By backing up and then organizing your digital photo files, you’ll safeguard them and make them easier to share with friends.