So now you’ve got all the equipment, you’ve got the knowledge, you’ve been shooting a lot to develop your eye, and now there’s only one ingredient missing. And it’s one that you generally will have absolutely no control over—luck.

There’s a great definition that says luck is preparation meeting opportunity. And I believe that to be so, especially when we’re talking about shooting underwater. If you develop the technical skills and if you develop the eye, when that rare opportunity presents itself, you’ll almost automatically know what to do and how to do it.

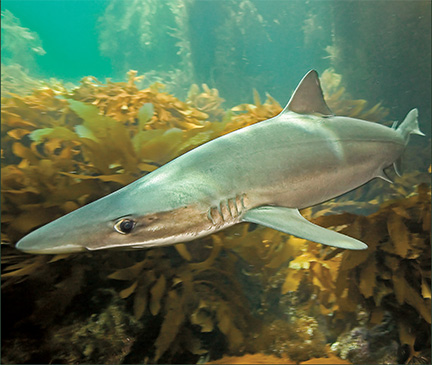

Every shot you see accompanying this article I would define as luck. I happened to be in the right place, at the right time, with the right equipment, and did the right thing. By the same token, you could also say that through years of experience and trial-and-error (and believe me, there’s PLENTY of error), I was able to put myself in the right place, at the right time, and was ready to respond with a set of skills that enabled me to get the desired result.

Take the sequence of the Spotted Moray Eel eating the Blue Tang. That was taken in Bonaire during a night dive. During previous night dives there, I knew that Blue Tangs were a frequent target of many predatory fish, and I also knew that the morays would hunt at night. I also knew that many of the predators, specifically the tarpon and the snappers, would hang on the edge of the pool of a diver’s light and strike at whatever animals happened through the beam. And armed with this knowledge, I had my camera already pre-set on an aperture/shutter speed combo, and with a strobe power, that I knew should produce decent results at night.

So my “default” setting for the camera that night was to be able to take that shot. When I saw something else, I’d re-set the camera, take the shot, and then go back to my default setting. And this plan paid off.

At some point during the dive, a blue tang strayed into the light. One of the snappers started tracking him and finally took a shot but missed. The tang, however, darted into a crevice… right where a spotted moray was lurking. In a flash, the eel came flying out of the hole, sand flying everywhere (talk about your backscatter problems…), and had totally wrapped himself around the tang. I remember thinking, “Oh my god!” and started pulling the trigger, all the while praying that everything would work.

In the span of maybe 60 seconds, the eel bit into the tang to get a better grip, unwrapped himself while holding the tang sideways is his mouth, gave one jerk of the head and flipped the tang around so the eel now had him by the head, and proceeded to swallow him whole and head-first. And I was there snapping away, waiting (for what seemed like an eternity) for my flashes to recycle, and realized I was witnessing a phenomenally unique experience.

Preparation meets opportunity. I was prepared and the opportunity presented itself.

With the shot of the pilot whales, we were in the Sea of Cortez and spotted them, following them in pangas and bailing out as a group in front of them. But usually they’d turn away from the group. So one time, after the group had bailed, I had the pangero drop me in a totally different spot. And sure enough, the whales turned from the group but headed straight for me.

Preparation meets opportunity.

For the close-up of the Panamic fanged blenny (also in the Sea of Cortez), I knew these animals were skittish but curious. And I knew that if I plopped myself down and starting shooting an animal, he’d scoot eventually, but he’d also come back to the same spot a minute or so later. So I shoot and he’d scoot. I’d inch closer. He’d come back. I’d shoot and he’d scoot. I’d inch closer. He’d come back. We repeated this dance over and over again for a good thirty minutes until I got the shot you see here.

Preparation meets opportunity.

I’ve said before that a photograph means you are capturing forever a moment in time that will never exist again exactly in that same way. That’s especially true underwater. It’s extremely hard to duplicate shots you may have seen (or taken) before because the conditions, whether it’s the movement of the water, the visibility, the light, the animals, or whatever, will never be exactly the same again.

You have a unique opportunity when you shoot underwater to create an image, good or bad, that no one will ever be able to duplicate exactly in that way again. Hopefully, this series has given you, if not the tools, at least sparked your curiosity to develop your skills, improve your eye, and start creating the photographs that will make everyone (even the editors of California Diving News) go “Wow!”