Digital photography, as great as it is, has turned us into sloppy photographers. With large capacity memory chips, we can shoot and shoot away with little consideration to exposure, framing and composition. More experienced photographers have overcome this tendency with better attention to the above mentioned details. But one important technique still seems to go disregarded—a full appreciation of the animal subject’s appearance, intricate detail, habitat, and behavior patterns. Knowing your animal subject intimately is key to getting the best photos possible.

I am not talking here about knowing scientific names, sizes, distribution, etc. I am talking about the color of the scales, patterns in the eyes, color of the inside of the mouth, what animals are in a symbiotic relationship, and what animals live on, or even in, your chosen subject. There is only one way to get to know an animal on this level and it is not through a camera lens. Here is a radical concept: On your next dive, leave your camera on the boat and just observe. Observe and look very closely.

So as to not miss that “one-in-a-million” shot, go camera-less on a somewhat “mundane” dive (if there is such a thing)—a dive with which you will likely see a lot of life, but nothing extraordinary.

Take a powerful dive light as you will want to study how the animal appears when fully illuminated. Unseen colors will pop out at you. The animals will also often shimmer and rainbow at different light angles and intensities. With this experimentation, you will get a better idea on how to optimize your strobe and camera angles.

Study the eyes. Often the eyes of fish, shrimp, octopus, even scallops, are the most interesting portion of the animal. It is in the eyes that we make a more direct connection with our fellow inhabitants of this planet. Many undersea animals have quite intricate designs, colors and pupils. The multi-faceted lenses of crabs, shrimp and other crustaceans are absolutely fascinating and beg to be captured in a digital or film image. But sometimes this escapes us when we are intently looking through the viewfinder. On your camera-less dive, look closely for these details.

Other details to look for are skin and scale textures, as well as subtle hue changes across the animal’s body. Many animals, and not just the octopus, will change colors according to moods, conditions, etc. Once again, use your light as a tool for the full effect and plan on how you will capture the fullness of color and texture on your next dive with a camera.

When we have a camera stuck to our face, we often miss out how undersea animals interact with each other in a common community. There is A LOT going on. While you do not necessarily need to fully understand why, only close patient observation, without the distraction of a camera, will reveal these behavior patterns. Mating and nesting behaviors are probably the most fascinating, followed by territorially, cleaning stations and feeding.

Take the ubiquitous garibaldi. Close observation reveals not only do they staunchly guard their nest of eggs, they do so in a specific pattern. They will confront an intruding diver in a head down position—excellent for the right kind of portrait of the face. They will also make a popping noise during a confrontation. Snap your fingers clothed in a red or orange glove and you can get a garibaldi to pose just about any way you’d like.

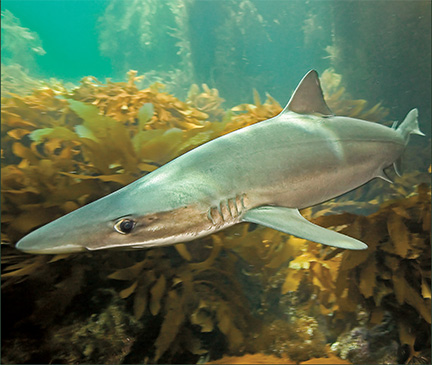

Photography is all about the light and not just the light from your strobes. You need a full understanding of how natural light acts underwater. Observe how it plays through the water, across the life and on to the bottom. Look at how the light is different on a sunny day as opposed to a cloudy day. Natural light is also different at different times of the day. Especially observe what kelp does to light. Kelp is semi-translucent. With the right angles, you can capture the slightly transparent blades, as well as their textures and even the animals that live on them. Study the overhead canopies shattering light into delightful beams.

To truly open your eyes to underwater photo opportunities, try making your next dive “camera-less,” and take the time to observe your subjects as never before.