Last month’s article pointed out that algae are classified as red, brown or green based on the color of their photosynthetic pigments and their evolutionary lineage. They all have chlorophyll a but only green algae look green. Other pigments mask green chlorophyll a in brown and red algae. In this article you will learn that basing an ID on the color of an alga in an underwater photo won’t always result in the correct classification. I thought I had several photos of green algae but it turns out I only have one.

Red and green algae are currently considered members of the Kingdom Plantae while brown algae (including giant kelp) are currently considered members of the Kingdom Chromista, which means “colored.” The number of species in these kingdoms varies according to the source. Seaweeds of the Pacific Coast says there are 8,000 species of green algae, 2,000 species of brown algae and 6,000 species of red algae. Most brown and red algae are marine. While green algae are more often found in freshwater, many live in saltwater and some are even terrestrial.

Last month I impetuously promised to explain how algae reproduce. Unfortunately, algae have numerous ways to ensure there are future generations of their species and most are rather complicated and technical, not to mention that they vary according to the species. So I’m going to renege on my promise: If you wish to know everything there is to know about algae reproduction, you are on your own!

In this article we will discuss one red, one green and three brown algae, including one that looks green. (Keep in mind that giant kelp, which is brown, looks green in many photographs.)

There are two photos of Scinaia johnstoniae. A red alga, it is red in one image and white in the other. But if you look carefully at the white phase, you will see a little bit of red at the base. The white S. johnstoniae is an older plant that is dying and its color has faded. The only thing I know about this alga is that it is supposed to be a southern, warm-water species. My photo was taken off San Clemente. While it is the southernmost Channel Island not many would describe its waters as “warm.” In the background of the red phase are masses of a brown alga, Dictyota coriacea, described in last month’s article.

Ulva sp. (also known as sea lettuce) is the only green alga of which I have a photo. The sp. means the species is unknown. Seaweeds of the Pacific Coast says: “Species of Ulva can be difficult to distinguish and are usually differentiated by characteristics such as the shape of the blade, presence or absence of perforations and small ‘toothlike’ projections on the edge of the blade.” Found in shallow waters from Alaska to Mexico, sea lettuce is abundant. A Living Bay says this seaweed is often fed to California brown sea hares being raised in aquariums (they are sometimes fed romaine lettuce). But while wild sea hares that eat a normal diet of the red alga Plocamium pacificum accumulate certain chemicals in their skin (and internal organs) that make fish regurgitate them, those raised on romaine or sea lettuce do not. Sea hares raised on Ulva are also inkless. Their normal diet obviously helps protect California brown sea hares from predators.

The next three algae discussed here are categorized as brown. Some of the blades of the Dictyopteris undulata pictured here look bright green, while those at its base look brown. Underwater, it often shows a milky-white iridescence over the brown blades. The photo is remarkable for the number of different animals in it, including purple gorgonians, bryozoans, solitary cup corals, multi-colored brittlestars, encrusting coralline algae and even a starfish that appears to be rummaging around the alga’s holdfast.

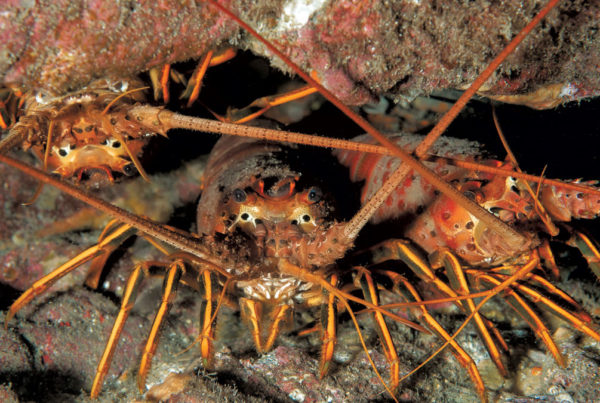

Sargassum horneri is an aggressive invasive species. All of those in the photo are juveniles. Like Sargassum muticum (discussed last month), Sargassum horneri is an Asian species. Its native range is shifting north owing to increasing ocean temperatures in southern Asia. A valued species there because fish reproduce, forage and seek protection in its beds and rafts, it is unwanted here because it competes with our native species. This brown alga was first seen off our coast in Long Beach Harbor in 2003. It was found off Baja in 2005 and between 2006-2009 was discovered living off Catalina, Anacapa, Santa Cruz and San Clemente Islands as well as Laguna Beach and San Diego.

Zonaria farlowii: This brown alga is one of 12 species in the genus Zonaria, a primarily tropical genus. The fan shaped thallus produces lobes that are outlined with a thin white stripe. The lobes can be nearly 10 inches tall and, to me, resemble a cabbage or certain succulents. Found off the California Coast from Santa Barbara to San Diego, Z. farlowii lives in shallow waters and tidepools. It is so hardy it can live buried under sand for several months. The one in the photo is surrounded by coralline algae.

Many algae are edible. Those collecting it for consumption should make sure it comes from a pollution free area and are urged to take no more than they can eat. Seaweed can also be bought in many grocery stores. Seaweeds of the Pacific Coast includes several pages of recipes.

The author wishes to thank Kathy Ann Miller, PhD, Curator of Algae, University Herbarium, University of California, Berkeley, for her help in the production of this article.

Red Algae

Classification

Phylum: Rhodophyta

Kingdom: Plantae

Class: Florideophyceae

Order: Nemaliales

Family: Scinaiaceae (Scinaia johnstoniae)

Green Algae

Classification

Phylum: Chlorophyta

Class: Ulvophyceae

Order: Ulvales

Family: Ulvaceae (Ulva sp.)

Brown Algae

Classification

Phylum: Heterokontophyta

(also known as Ochrophyta)

Class: Phaeophyceae

Order: Dictyotales

Family: Ulvaceae (Ulva sp.)

Order: Fucales

Family: Sargassaceae (Sargassum horneri)