For many sea creatures parenting is easy; they have little or no contact with their offspring. Take for example, the California spiny lobster (Panulirus interruptus). Found off the West Coast from Monterey Bay, CA, to Magdalena Bay, Mexico, this is the succulent crustacean that causes a diving frenzy known as Lobster Season. Ever wonder why the season is closed between the middle of March and the end of September? Read on and I’ll enlighten you!

To ensure his species’ survival, the male spiny has only one task, carried out between November and May each year: mating with as many female lobsters as possible, depositing a spermatophore—also called a “plaster—on each of their sternums. You may have seen plasters on the undersides of bugs but not known what they were. White and sticky when fresh, they turn black and harden in a few days.

Lobsters reach sexual maturity at five to six years of age, and legal size (a carapace measuring 3.25 inches in length) when they are 7 to 11 years old. Mating takes place in 50 to 100 feet of water.

Between May and June, the female moves to waters less than 30 feet deep. When she is ready to spawn, she uses pincers on her fifth pair of walking legs (males lack these pincers) to break open the plaster so the sperm inside can fertilize the 80,000 to 800,000 coral colored eggs she releases from ducts at the base of her third pair of walking legs. The eggs adhere to her fan-shaped, multi-layered swimmerets (much larger and more complex than the male’s).

The larger the female, the more eggs she can carry and the more she produces. There has to be such a large number of eggs because the young have a long and perilous path to adulthood.

The female’s parental duties last only until her eggs hatch in nine to ten weeks. The tiny, transparent pelagic larvae (.06 inches long) have large, pigmented eyes, flattened bodies and long legs. They bear little resemblance to their parents. In the next seven to nine months, they will drift with the currents, eating plankton and, if they don’t get eaten themselves, molting 12 times.

According to California Fish and Game literature, “lobster larvae have been found as far as 350 miles offshore and as deep as 400 feet below the ocean surface.” Only three percent of the hatchlings are estimated to reach Stage 11, at which point they look somewhat like their parents and are about 1.14 inches long. From May through September these larvae swim to shallow water and settle to the bottom. After their next molt, 9 to 11 days later, they look like miniature adults.

It is my hypothesis that juveniles abound at San Clemente Island, the southernmost Channel Islands, because it has the first shallow coastal waters Stage 11 larvae encounter as they drift with the currents. Juveniles seek shelter in areas with surf grass, southern sea palms, bushy brown algae and kelp (also abundant at Clemente), subsisting for the most part on amphipods, isopods and vegetal material.

Adult P. interruptus have a varied diet that includes fish, sea urchins, clams, mussels, scallops, sea stars, snails, worms, kelp, algae and even other lobster. Several years ago I watched an extraordinary presentation by a student at USC’s Wrigley Marine Science Center on Catalina. She (or maybe he) set up time-lapse cameras on Bird Rock and, during low tide at night, captured images of lobster coming out of the ocean to feast on mussels growing on the rock.

Several fishes, along with octopuses, moray eels and horn and leopard sharks, prey on lobsters.

Lobsters must shed their outer shells (exoskeletons) to grow. According to Seashore Animals of the Pacific Coast, “…the body shrinks away from the exoskeleton before it is withdrawn, and the animal escapes through an opening formed on the upper side between the carapace and the first abdominal segment.” About 40 molts occur before the lobster reaches legal size and weighs about a pound. Male lobsters grow faster, live longer and get larger than females. The biggest one on record was three feet long (excluding antennas) and weighed 26 pounds (wouldn’t we all love to see one of those!). It is estimated that male spiny lobsters can live 30 years or more, females up to 20 years.

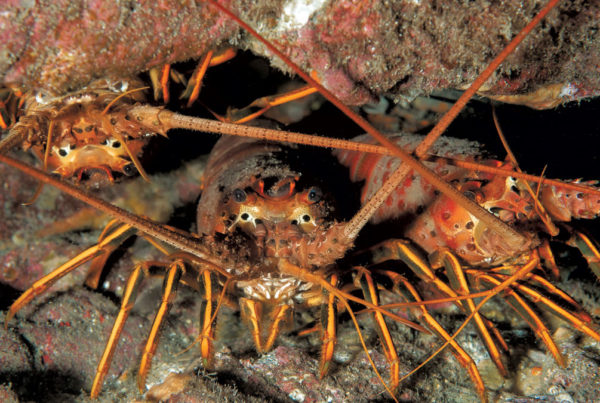

During the winter, most lobsters are found offshore at depths of 50 feet or more. In late March, April and May, they move closer to shore in warmer waters less than 30 feet deep. They move after dark in small groups.

So, why is lobster season closed between the middle of March and the end of September? To prevent female lobsters from being taken while they are “berried” (i.e., egg-bearing), as well as to protect newly molted lobsters. (You knew that, didn’t you?)