There are some fundamental decisions you need to make in order to give yourself the best possible chance of getting a good photo, and a lot of those choices are about equipment. Although I normally shoot with a top-of-the-line SLR, a variety of lenses, and dual flashes, one of my favorite photos (of a squid forming an egg sac and burying it in a pile of other eggs) I took with a borrowed disposable one-time use camera in an inexpensive housing and single strobe.

Don’t discount the value of developing a good “eye.” You must develop an understanding of what’s going to look good and what isn’t. You do that by taking LOTS of pictures, analyzing what works and what doesn’t, and developing technique. As I like to tell my photo students, you can buy the best equipment in the world, but if you never develop an eye, all you’ll end up with is technically perfect crap.

Even so, the equipment we choose will affect what we’re able to shoot. The obvious example would be that it’s tough to get a good shot of a whale shark if you’ve got a macro lens on. Likewise, its hard to shoot a pygmy seahorse with a wide-angle lens. So let’s take a look at what the options are.

Although you would think the first thing to look at would be the camera, I think that’s fairly irrelevant. The reason is that, unless you’re highly paid pro, you’ve probably only got one camera to choose from. You’ve got what you’ve got. And you can take great pictures with a digital or a film camera, an SLR or a fixed-lens, etc. Your camera may place certain limitations on you, but unless you’re thinking of buying a new one (and even then, you’ll simply have a new set of limitations), camera choice doesn’t matter that much.

What DOES make a big difference is lens choice. Some cameras do not have interchangeable lenses so you’re stuck with whatever the focal lengths are. However, if you do have a choice, either because you are shooting with an SLR or have the option of a supplemental lens, the lens choice you make is important.

I shoot with a variety of lenses with my SLR: 20 mm fixed, 18-35mm zoom, 28-105mm zoom (my favorite because it gives me the most versatility), and a 105mm fixed macro. The lenses that I choose affects what my potential subject matter can be. And lenses choice will be based on not only what I’d like to shoot but also on what the water conditions will be.

Remember that one of the keys to a good photo is to put as little distance between you and the primary subject as possible. You’ll get better color saturation, your flashes will be more effective, and you’ll minimize the effect of particulate in the water. You’ll also see more detail in a close-up animal than in one far away.

So it means when choosing a lens how close the lens will focus becomes a key factor. Most of my lenses will focus down to a minimum distance of anywhere from 9-16 inches. This distance is measured from the film plane, or light sensor in the case of digital, in the back of the camera, NOT from the front of the lens. I won’t buy a lens that won’t focus down to that general distance. That means I have the option, if the animal will let me, of getting almost right on top of my subject.

But assuming all your lenses fit the criteria, now you have to decide which one to use. And even if you have a fixed-focus lens or a zoom lens that’s built into the camera (and many digitals are today), it’s still a decision you have to make. What range of the lens will be useful? Will you be limited to macro? Can you shoot wide-angle?

Water clarity and available light play a big factor in making this decision. In Southern California’s outer islands, the first dive is usually around 7 or 8 a.m. Not a lot of light available at that time because the sun is still low on the horizon and the light penetration may or may not be good for photos. Sometimes on the first dive, I’ll take down a macro lens and not even bother with trying for anything wide.

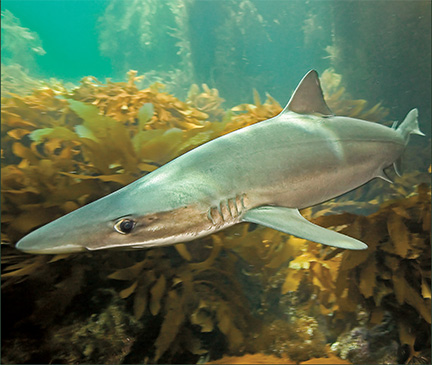

If you get decent sunlight in the water column (usually 10 a.m. – 2 p.m. is considered best, but there’s really no hard-and-fast rule) and especially if there’s no or limited particulate, then a wide-angle lens can produce some stunning results.

Once you make your lens choice, realize that two things are going to happen. The first is that you’ll get some good opportunities to shoot the animals you wanted. And the second thing that’s bound to happen is that you’re going to see something that’s going to make you wish you’d chosen a different lens.

I remember diving the Eureka Oil Rig one time and being set up for macro. It was a gorgeous day with 100-foot viz. And while I’m was looking for blennies, and anemones, nudibranchs, and other tiny guys to fill my frame, I turned around to see—much to my sensory delight and photographic dismay—SEVEN (!) mola-molas cruising the blue just off of the rig. Now if I wanted to shoot a mola-mola eyeball, I was all set…

Okey-dokey. So you’ve got your camera. You’ve got your lens (or lenses). Now you’re ready to go shoot, right? Naw! There’s plenty more decisions to make! More on that later.