A glass globe of the earth sitting in sand of a beach with waves crashing in the background.

Political borders are essentially meaningless to marine life, as they can swim or drift across them without concern. Recently several marine critters have entered into southern California waters, including Catalina, as somewhat natural range extensions through dispersal. I find these new arrivals of great interest. Fish such as barracuda, yellowtail, tuna and even tiny anchovy can migrate through active dispersal, swimming into new or seasonal habitats. Others, such as marine invertebrate larvae and the eggs and larvae of fish not strong enough to swim long distances, rely on passive dispersal in currents. Drifting kelp rafts can transport invertebrates and fish over significant distances, as my research back in the 1960s and 1970s demonstrated.

Once these critters arrive in a new habitat, they face the challenge of “naturalization” or as we biologists refer to it: ecological and reproductive establishment. For a southern species to adapt to life in our more temperate seas requires several things. First, the water temperature throughout the year should be within the survival range for the species. Some species with wide depth ranges farther south can find acceptable conditions in shallower waters here.

It must also find adequate food sources in the new habitat. Some critters are highly selective in what they will eat, and are more likely to starve in a new environment. Scientists have noted that some generally herbivorous southern species like halfmoon and opaleye may add invertebrate protein to their diet in our cooler waters. Animals that are generalists and tolerate a wider range of food are more likely to find something palatable on the local menu. The young must also find appropriate foods to allow them to grow to maturity.

Individual survival is one step in adapting to a new location. However, for the species itself to persist there, and thus expand its geographical range, there is another critical factor. Water temperatures must be in the proper range to induce mating and support the development of the eggs, larvae and young. This is often a critical factor for any species arriving here.

Species from farther north can also adapt to our warmer waters through submergence. They merely descend to deeper depths where temperatures are more appropriate for them. Of course this may put them below normal diving depths and prevent their detection by most scuba divers. The Wave of Migration Over my lifetime, “immigrants” into Catalina waters from south of the border have included the scythe butterflyfish, finescale triggerfish, Guadalupe cardinalfish, plain cardinalfish, California moray, Argus moray, whitetail damsel, largemouth blenny, Panamic fanged blenny and green sea turtle just to name a few. Some have been successful in establishing themselves here long-term, others have not. So what is triggering this wave of migration? In large part it is ocean temperature change. It is well known that some species such as painted greenling (Oxylebius pictus), many rockfish (Sebastes spp.) and red sea urchins (Mesocentrotus franciscanus) have a northern, cooler water affinity while others such as garibaldi (Hypsypops rubicundus) and crowned (black) sea urchins (Centrostephanus coronatus) prefer warmer southern waters. As sea temperature changes over time, this can affect the geographic range of species with specific temperature requirements. An interesting set of experiments has been conducted up at Stanford’s Hopkins Marine Station. From 1931 to 1933 Stanford graduate student Willis Hewatt studied the intertidal invertebrates along an intertidal transect line. Then, from 1991 to 1993, Rafe Sagarin duplicated this study using the exact same transect line. He found that six of eight northern species had declined over the nearly 60 years and 10 of 11 southern species had increased.

Water temperatures at the study site had increased 1.3° F over that period with summer temperatures nearly 4° F higher. Sagarin attributed the changes in species composition to the increase in ocean temperature due to climate change. He ruled out any significant effect from shorter-term fluctuations such as El Niño or the unusual warm water events of recent years known as The Blobs.

The same factors are at work here in southern California, already a transition zone between northern and southern biota. Having studied marine biology at Harvard back in the 1960s when Dr. Roger Revelle was teaching there, I was aware of global warming (as was my classmate Al Gore). However, I didn’t have the forethought to establish a similar study area here on Catalina when I arrived back in 1969. It certainly would have been interesting to see the changes in marine invertebrates and fish in our transitional zone. Interesting Observations One interesting case of immigration from the south is a species widely believed to be well established in our waters. I’m referring to the California moray (Gymnothorax mordax). Although these fish are seen frequently by divers, ichthyologists believe they are incapable of reproducing in our cool waters. Instead, apparently pulses of long-lived leptocephalus larvae produced off Mexico, where water temperatures are above their minimum temperature for reproduction, continually restock the population in our waters. If true, and ocean temperatures continue to rise, reproduction may begin to occur in our waters in the future.

Back in 2004 diver Chris Menjou photographed an Argus or white spotted moray (Muraena argus) in the Casino Point dive park on Catalina. Although this moray, whose normal distribution is much further south than the California moray, seemed to be surviving fine; it lacked a critical factor in becoming established here. It had no known mate! Even if it did, water temperatures here are probably below its minimum reproductive temperature.

Early arrivals here from down south include the northern scythe or scythemarked butterflyfish (Prognathodes falcifer). This species has been present in Catalina waters for many decades and is believed to have arrived initially during an El Niño event. Although many believe it to be a warm water tropical species, it is found in cooler waters as deep as 800+ feet off Mexico.

Over the past two decades I have filmed juveniles of this species at the Empire Landing Quarry. This suggests that they have become reproductively established in our waters and it has been noted that their distribution around Catalina has been expanding. A possible alternate hypothesis is that its local population is being supplemented by pulses of larvae coming from down south. However, I feel pretty confident that reproduction is indeed occurring here.

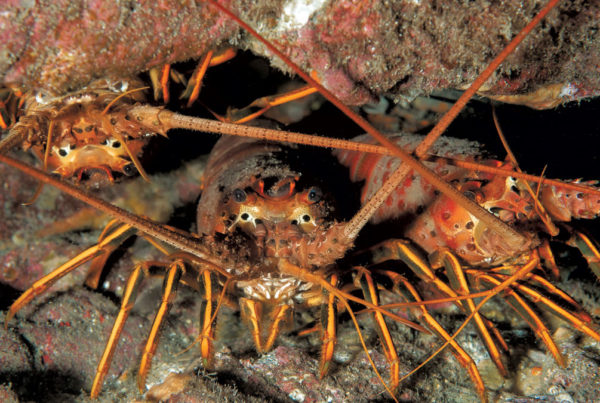

Another early arrival in Catalina waters is the finescale triggerfish (Balistes polylepis). Like the butterflyfish, this species may also be found in very deep waters off Mexico, allowing it to easily adapt to our cooler waters. Having survived as a species here for several decades there is still some question as to whether it is reproductively established. Some divers have reported seeing young triggerfish here, and their range around Catalina also appears to be expanding. However Dr. Milton Love reports a decline in other regions of southern California and suggests the population may be sustained by infrequent larval recruitment. In 2001 I filmed what I believed to be a Guadalupe cardinalfish (Apogon guadalupensis). Several years later I encountered a number of plain cardinalfish (Apogon atricaudus) in the dive park. These two species are not easy to distinguish unless the first dorsal fin is at least partially erect. The plain cardinalfish has a black streak in the middle of that fin while on the Guadalupe it is absent. Pink cardinalfish (Apogon pacificus) are also known to be present in mainland waters although I have yet to see one off Catalina.

I have followed these fish for a number of years now. During the day they tend to hide near the reef, but at night they come out in the open to feed. They are mouthbrooders and on a number of occasions I have captured images of males brooding the eggs in their mouths. The young appear to remain close to the parents as I have noted dozens of them in the same reef crevices. Certainly this species appears to have ecologically and reproductively established itself here.

Back in 2012 Ken Kurtis noted a juvenile damselfish below the stairs at the dive park. I was quickly able to identify it as a whitetail damsel or gregory (Stegastes leucorus leucorus). It disappeared that winter but three years later I discovered a late juvenile or early adult individual and reported it in the September, 2015, issue of California Diving News as a probable reappearance. These were the first known sightings of the species in California waters. Sadly, like the Argus moray, it had no mate and therefore no chance of extending its range into our waters permanently.

In 2016 diver Ruth Harris spotted a Pacific seahorse (Hippocampus ingens) out on the old “swim platform” in the dive park. I was able to get some decent video of it, but it disappeared the following day. They are known from Pt. Conception south to Chile, but this was the first sighting I’d had in Catalina waters in nearly 50 years.

That same year there were reports of unidentified fish in the rocky rubble to the left of the dive park stairs. I located several and tentatively identified them as largemouth blennies (Labrosomus xanti). Dr. Milton Love confirmed the identification with the proviso that it was also possible they were multipore blennies (Labrisomus multiporosus) but that a specimen would be necessary to determine which it was. Since the park is a marine protected area, I could not collect one.

An individual of this species had been sighted elsewhere on Catalina and several others were spotted in the San Diego area. Formerly known only as far north as Guadalupe Island, these sightings were the first time the species had been seen in California waters. On one dive alone I spotted 18 individuals of both genders and the males were mostly in reddish-orange courtship coloration. A recent report to me by Anastasia Laity indicated that there is a good population of them at Hen Rock further up our coast. This year diver Karen Shine described behavior she had observed between a male and three females, which sounded like courtship to me. Milton Love confirmed it was typical pre-mating behavior. So far no little ones have been sighted, but I’m keeping an eye out.

In 2017 Ruth Harris again reported two unidentified “strangers” in the park. Shortly after that I independently observed a blenny I was familiar with from south of the border, the Panamic fanged blenny (Ophioblennius steindachneri). I showed pictures of the ones I filmed to Ruth who confirmed it was the same species she had seen. They were fairly large and must have been in our waters for a while before being discovered. I only saw three of these fish last year and have yet to see them this year.

Lastly there have been multiple sightings of green sea turtles (Chelonia mydas) over the past decade or so, both in the dive park and elsewhere around Catalina. Captains on the glass bottom boats have seen as many as five at one time in adjacent Lover’s Cove and some people have claimed to see turtle tracks at sandy beaches on the island’s windward side. Their presence off Catalina is not a huge surprise since there are colonies of them in San Diego and the Orange County coast. However they do make for an interesting encounter here.

Ecosystems are dynamic, always changing. There is often some new behavior or species to witness. All one has to do is keep an open eye and research what you see. Therefore it is important to establish regular baselines to document changes in species, populations and ecosystems. It is because of this that I have kept diving for 56 years, 49 of them here in SoCal. Of course if ocean temperatures continue to rise and this trend persists, I myself may have to evolve from a kelp forest ecologist to a coral reef one!