Photography is a means of expressing one’s creativity. A photographer exposes light to film just as a painter applies paint to canvas or a sculptor applies chisels to stone. However, the greatest masterpieces usually do not happen by mere chance. Usually a great deal of preparation precedes the final art form. Creating an underwater masterpiece is no exception.

Since everyone is different, creativity manifests itself through a variety of ways. My motivation usually comes from viewing a roll of slides on a light box of a dive recently made. That is usually where I see the opportunity to make a good shot a great shot. Please realize that photography, like any other form of art, is very subjective. So do not be discouraged by the opinion(s) of other critiquing photographers, for one man’s rose may be another man’s thorn.

The first step in the preparation for the final shot is to set a realistic goal. One cannot expect to re-enact a once-in-a-lifetime diving experience. Therefore, it is very important to be patient and well prepared. Realize the fact that the final image will not come to you. Getting into the water on a regular basis with your camera will increase your chances significantly, although one never knows when that fleeting opportunity might ever again present itself.

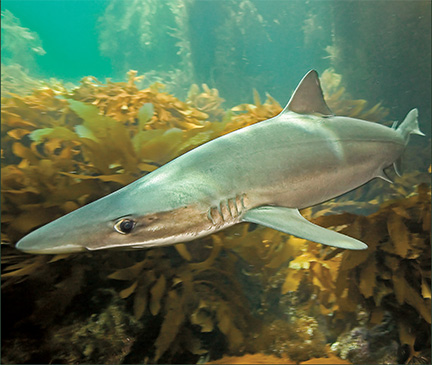

Another consideration is the shot’s key elements: diver, fish, kelp, sun, etc. This is perhaps one of the hardest parts of the whole plan, especially if the photo shoot includes multiple key elements. Generally, the more key elements involved in the photograph, the more impact the image will have on the viewer—and the harder to choreograph. However, too many elements can be very distracting, leaving the viewer overwhelmed with too much information. Then, the true genius of a potentially great shot can be muddled or lost entirely.

It is my opinion that an image that tells a story has far greater impact on viewers. For example, a clean, well-exposed photograph of a moray eel may make for a very nice shot, but a photograph of a moray eel with one or two cleaner shrimp grooming its dental work will make for a much better final print.

The next part of the equation is to figure out what lens, film, and lighting is needed to create the image. Some camera manufacturers, have tried to make this easier by developing a camera system which allows a photographer to interchange lenses underwater, but many other camera systems require a decision as to how to best shoot pictures before even getting into the water, where Murphy’s Law is sure to takes its toll. Inevitably, the camera is fitted with a 1:2 tube and framer, and a playful sea lion suddenly appears and just won’t go away. This is not a time for frustration; rather, it is a time to enjoy the encounter and realize the potential photographic possibilities the next time this situation presents itself.

If a diver is the key element in the photo session, inform them that they are a key element. Very few stunning images involving a model are not planned out in advance. Exceptions are “happy accidents,” and when they do happen, I would encourage that lucky photographer to buy a Lotto ticket on the way home because good things may be headed their way. Communication with a model is key here. Discuss the shot, perhaps taking pencil to paper and draw a rough sketch or maybe develop a couple of hand signals to allow both photographer and model to better communicate when underwater. Whatever is decided, preparations need to be discussed prior to entering the water.

If Mother Nature’s help is needed in providing key elements for a masterpiece, it is once again time to be realistic. If a beaming sun is part of the equation, don’t expect to see it on a cloudy day. If good visibility is necessary to make the image, perhaps plan on making the shot when visibility is best.

If the session requires the cooperation of marine life, this is where the equation gets tricky. Garibaldi, for instance, can be found just about anywhere in the ocean off the coast of Southern California, but making a garibaldi fit into the photographic masterpiece the way it is envisioned may be out of your hands. Baiting and/or teasing marine life, whether one agrees with the practice, is the only bit of control one has over this key element.

Then, if and when all the key elements that you have imagined in your mind’s eye present themselves at the same time, do not spare the film! Take as many pictures as possible because such an opportunity, where all your key elements have come together, for they may never present itself again. Do not look at shooting an entire roll to be a waste of film. Instead, look at it as an investment of film. After all, at this point the film is the least expensive item in the equation.

Lastly, and for many this will be the hardest part—and be honest with yourself—was the final image what you had envisioned? Friends and family at this point are no help. They will have a tendency to be supportive and not offer the constructive criticism a budding underwater photographer needs. Only the photographer can make the gut-wrenching decision of whether to keep a picture or pitch it to the circular file. If the results are not up to expectation, this is not the time to quit. Rather, it is a time to re-evaluate all images taken and find room for improvement so the same mistakes will not recur.