Fish have basically two personality types—those that flit around the reef in a nervous, almost psychotic fashion; and those who are calm, relaxed, and confident. In California waters one of the most relaxed and approachable fish you will encounter is the lingcod.

Biologists place lingcod into the Class Actinopterygii, the ray-finned fishes. These are called ray-finned because their fins are webs of skin supported by bony spines (“rays”), as opposed to the fleshy, lobed fins that characterize the class Sarcopterygii. They are further classified into the Order Perciformes, meaning perch-like. This is the largest Order of vertebrates, comprising over 7000 species and includes about 40 percent of all bony fish.

Lingcod belong to the Family Hexagrammidae, the greenlings, and this family contains 12 species in 5 genera. The largest member of the greenling Family is the lingcod, Ophiodon elongates, meaning “elongated snake tooth” and is the only member of the genus. It is easy to see how lingcod received this scientific name considering their large mouth with large canine teeth. They should not be confused with the unrelated Atlantic cod.

They are found from Alaska to Baja, from the intertidal down to 2,700 feet, although they are most abundant less than 350 feet. Lingcod may grow to 5 feet and 105 pounds, and the females are generally larger than males. They have a blotchy, mottled skin that often has a bluish or greenish tint. Older lings often take on a bright yellow color. Lingcod occasionally have a light green or blue color to their fillets. This color is due to their diet and in no way indicates that the fish is bad. In fact, the color always disappears on cooking.

Juveniles are migratory, and may travel as much as 25 miles. Adults are very territorial and most fish, particularly the males, move around very little. During most of the year there is a segregation of sexes with the smaller males being found in shallow water less than 100 feet deep, while the females are often in water exceeding 100 feet and often to 400 feet. Because of this depth segregation, some 70 percent of all lingcod observed by divers are males.

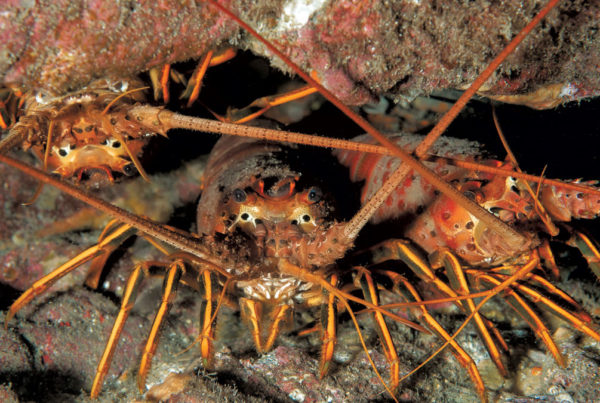

This situation changes in winter when they move inshore to breed. Starting in October, lingcod migrate to nearshore spawning grounds. The males migrate first, and establish nesting sites in rocky crevices or on ledges. Spawning takes place between December and March, and females leave the nest site immediately after depositing eggs. Males actively defend the nest from predators until the eggs hatch in early March through late April. Lingcod are polygamists and a single male may guard as many as four nests during the seven-week incubation period. This househusband will aggressively protect the egg mass from predators, mostly crabs, and rockfish. Should the male be killed, his eggs will be rapidly consumed.

The larvae are pelagic until late May or early June when they settle to the bottom as juveniles. Initially they inhabit eelgrass beds, and eventually move to flat sandy areas that are not typical habitat for older lingcod. They eventually settle in rocky habitats, but remain at shallow depths for several years.

Young fish feed mostly on crustaceans. Adults are voracious predators and feed on anything that moves, although they prefer juvenile rockfish, squid and their favorite food appears to be octopus. They lie in wait for an unsuspecting prey to wander too close and then pounce on their dinner with razor sharp teeth.

Often when a diver encounters a lingcod they will sit very still, as if they believe they are invisible, or are very confidant. Egg-sitting males are very difficult to dislodge from their nests. Lingcod are one of the most sought after fish by California divers, and are second only to combined species rockfish, genus Sebastes, and about 6 percent of the sport harvest is taken by divers. Their behavior makes them very easy targets to spear.

Alas, over fishing has taken its toll and there are drastically fewer lingcod today than a decade ago. This has resulted in fishery closures and restricted seasons all along the West Coast. If you wish to hunt them, make sure you know the current regulations as they change frequently.