Once again we dive into Cnidaria, a large phylum that contains approximately 10,000 species. Phylum members include many animals that attract attention because of their bright colors: sea anemones, corals, sea pens, gorgonians and jellyfish. These creatures can afford to flaunt their beauty because most of them have defensive polyps loaded with nematocysts (also called cnidocytes) that can fire venomous miniature harpoons. Lucky for us, most of these weapons are too tiny to penetrate our skin.

Cnidarians currently belong to one of four classes: Anthozoa (sea anemones, corals, sea pens, gorgonians); Scyphozoa (jellyfish); Cubozoa (box jellies) or Hydrozoa (hydroids, hydrocorals, siphonophores, hydromedusas, Portuguese man-of-war). Two additional classes may be created in the near future.

The focus of this article is the amazingly diverse animals called hydroids, of which there are about 350 species. According to A Living Bay, they were once called zoophytes, or “animal plants,” because they “combine a plantlike appearance with …animal traits.”

Hydroids are often colonial and the sexes are separate. Thus, a colony is either male or female. Most hydroids are carnivores and have three types of polyps: feeding, defensive and reproductive. It is the feeding and defensive polyps that are armed with nematocysts. Venom from them immobilizes what they hit.

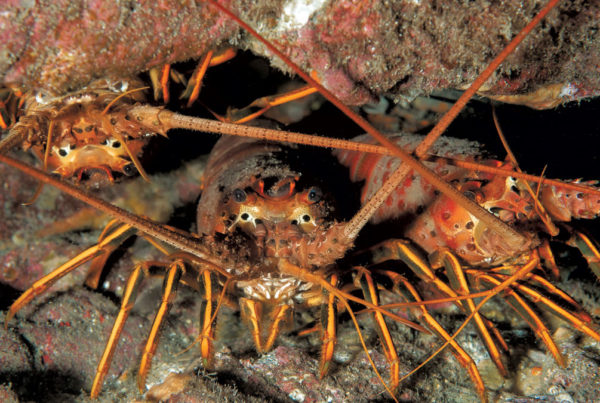

The variety of hydroids is apparent with just a glance at the photos here. Only two are positively identified. All we know about the creatures in photos three and four is that they are of the genus Plumularia, species unknown.

Ostrich plume hydroid (Aglaophenia struthionides):

I always wondered what the “beads” attached to this hydroid were. And now I know. They are called corbulae, contain medusoids and are quite amazing. Male medusoids release sperm that fertilize the eggs of the female medusoids. These hatch into tiny larvae that settle down on the substrate and morph into a polyp that starts a new hydroid colony.

Ostrich plume hydroids have feather like plumes that branch off a central stalk. They can be five inches tall. These animals are found from Alaska to Baja, on rocky substrate and from intertidal waters down to 500 feet.

Orange hydroid (Garveia annulata):

Photographed here growing among the branches of an articulated coralline alga, this hydroid is easy to identify. The colony has 20 to 30 polyp-covered stems and can be six inches tall. It ranges from Alaska to SoCal and can be found from intertidal waters to depths of at least 400 feet. A male colony’s reproductive polyps release sperm that fertilize the eggs in the reproductive polyps of a female colony.

The orange hydroid Garveia nutans is identical to Garveia annulata except that it lives in the British Isles.

The author wishes to thank Genny and Shane Anderson for their help in the preparation of this article.

Hydroid Facts

Ostrich plume hydroid

Phylum: Cnidaria

Class: Hydrozoa

Order: Leptothecata

Family: Aglaopheniidae

Genus/species: Aglaophenia struthionides, formerly Plumularia struthionides

Orange Hydroid

Phylum: Cnidaria

Class: Hydrozoa

Order: Anthoathecata (same order as hydrocorals)

Family: Bougainvilliidae

Genus/Species: Garveia annulata

The Genus Plumularia

Phylum: Cnidaria

Class: Hydrozoa

Order: Leptothecata

Family: Plumulariidae

Genus/Species: Plumularia sp