Underwater photography can be a challenging adventure. You must keep the inside of your camera dry, deal with low light levels, and visibility that is measured in feet instead of miles. Not to mention that the sea is always in motion, making it difficult to compose even stationary subjects. And then there are those subjects that swim. Yes, fish portraiture is the most difficult of all wildlife photography. What follows are tips to get better fish portraits.

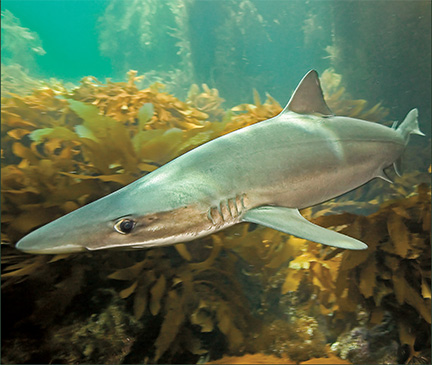

To begin, I must define a fish portrait. A portrait is not simply an image of a fish. It goes deeper than that. A portrait should reveal something about the fish—what it is feeling, a glimpse into its personality, its behavior, perhaps its soul. The gleam in the eye, the position of the fin or mouth may make a subtle, but noticeable, difference between a portrait and a snapshot.

I characterize my potential fish subjects and approach based on experience and knowledge of fish behavior. The easiest subjects are those who think they are invisible or are engaged in behavior that makes them reluctant to leave the area. Examples of this are fish being cleaned, fish sitting on a nest, living in a hole, or sleeping. California fish that fall into this category are eels, lingcod, cabezon, and garibaldi. You should approach the fish slowly while avoiding direct eye contact; look at them from the corner of your eye and not directly with both eyes. Then just sit there for a little while until the fish becomes comfortable with your presence. Look for signs that you’re are too close—tense body posture, rising up on two fins in preparation of a quick departure. Only after the fish is relaxed should you begin shooting.

Nervous fish that are constantly in motion are very difficult to photograph. Señoritas and blacksmith fall into this category. It is best to sit in one place and let these fish come to you. These fish will often come quite close and then suddenly dart away. Remember that they will often hesitate for just an instant before they split. Learn to anticipate this hesitation and click the shutter when it happens. Also, watch the fish from a distance. Many fish exhibit some form of repeat behavior. Learn to look for the pattern and position yourself to be in the right place when they pass by.

Remember the photographer’s mantra—get low, get close and shoot up. This camera position will minimize the water and backscatter between you and your subject and isolate your subject from the background. I don’t bait fish for photos (sharks are the only exception). A magic moment occurs when the fish becomes interested in me, in my camera, or its reflection in the camera port, and that moment rarely happens with bait in the water.

For fish photography a housed SLR system is much better than a rangefinder system. A fish will normally not allow you to place them in the jaw-like focusing aids needed for rangefinder cameras. A housed SLR system with a 50 or 60mm-macro lens is an ideal, all-around lens for fish photography. The 100 or 105mm-macro lens will allow you to photograph little fish at a greater distance.

The final tip is to dive and photograph a lot. The more time you spend in the water, the more you will learn about fish behavior and the more opportunities you will have for that great shot. You will also encounter more “brain damaged” fish; you know—the ones that are willing to pose.