We are lucky, you and I, that giant kelp (Macrocystis pyrifera), the largest kelp in the world, grows off our coast. Swimming through a kelp forest on a sunny day when the water is clear is an awesome experience, as magical as cruising through a redwood forest on land.

Giant kelp is a type of brown algae that can grow up to 24 inches a day and attain a maximum length of 175 feet under ideal conditions. While it is known to live at least six years, the blades have a life span of only six months, continually dying off and being replaced.

M. pyrifera doesn’t have roots and is anchored to the bottom by a holdfast comprised of haptera, which look like roots and cling to rocks or even such things as tubeworms. (To me, a holdfast resembles a mass of multi-colored spaghetti.) New haptera are blue, purple, pink or red, becoming yellow-brown as they age. The larger the holdfast, the older the plant. Rising from the holdfast are the stem-like stipes and from them, fronds (also called blades).

Giant kelp would waft about on the bottom of the sea without the gas filled bladders—pneumatocysts—that keep the stipes and blades afloat.

The part of giant kelp that lies on the surface is called the canopy.

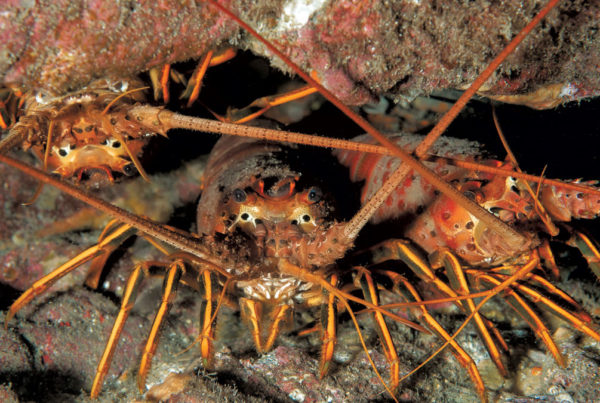

Animals live on all giant kelp parts. According to one book in my library, The Amber Forest, more than 175 species live in holdfasts, including the juveniles of many fish. There are also shells (even abalone), brittlestars, shrimp, crabs, anemones, sea urchins and starfish, among others. The authors of the book point out that swell sharks may anchor their egg cases to haptera.

Examine kelp blades and pneumatocysts and you’ll find tiny bryozoan and hydroid colonies, isopods, amphipods, mysids, anemones, nudibranchs and mollusks, including the Norris topshell with its bright red and black animal.

Some animals, most especially fish, hide and hunt among the stipes and blades of giant kelp and under its canopy. Other animals—most notably sea urchins—eat kelp. The Birch Aquarium at Scripps website contains extensive information on kelp, including this: “Approximately 800 species of marine organisms depend on the kelp forests at some point in their life history.”

Giant kelp was first harvested off the Southern California coast in the early 1900s and the crop peaked in the 1970s. Then it was common to see (and hear underwater) huge kelp harvesters working off San Clemente Island. The California Department of Fish and Game licenses commercial kelp harvesters and regulates their take, allowing the plant to be cut no deeper than four feet below the surface.

Kelp was once used as a fertilizer, then to make gunpowder and as an animal feed. Today, the algin derived from giant kelp is used in a variety of products: paints, cosmetics, cheese, asphalt, rubber tires, polishes, toothpaste, ice cream, paper, ceramics, charcoal briquettes, and medicine.

Giant kelp prefers temperatures of 50 to 65°F. If the water gets and stays warmer for any length of time, it will die. According the Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute website, giant kelp is found along the West Coast from southern Alaska to Baja California and along the temperate coasts of South America, South Africa, New Zealand and Australia.

When I was a new diver, I was apprehensive about diving in kelp, fearing entanglement. That was before I learned how easy it is to bend and break the stipes and to kelp-proof my gear. I also discovered that if I swam through natural gaps in the forest I wouldn’t get entangled in the first place.

Many divers have wonderful buoyancy control and can hover effortlessly in mid-water on their safety stops. Since I have yo-yo tendencies, I make my safety stops holding onto a bunch of kelp stipes. No wonder I consider kelp both beautiful and diver-friendly.