Chances are, you’ve watched the Netflix original film, My Octopus Teacher, which won the 2021 Academy Award for Best Documentary Feature. The film chronicles a man’s relationship with a common octopus in a South African kelp forest. I had a similar experience right here in our local waters at one of my favorite dive sites, Topaz Street in Redondo Beach. I had been cardio snorkel-swimming and freediving the jetty at that location when I found an octopus just outside its den. Over the next few months, I observed the octopus, which I named Spot. I came to learn its habits and behavior patterns. Spot would move around at dusk across the small reef and out to the shallow stubs that are the remains of pier pilings. Pockets in the rotting wood would give the octo protection as it ventured across the sand in search of small clams. Finding a snack, Spot would then carry it back to its den to pry it open and munch away.

I eventually decided to get closer by using scuba. Bad idea. It set our relationship back a month. Did I just say “relationship”?

Finding Spot hunkered down in his den I was able to relax close by observing for hours with my big tank in the shallow water. Eventually Spot moved closer to the entrance but I never saw him venture forth again. Even so, it was those encounters at his home entrance that meant the most to me.

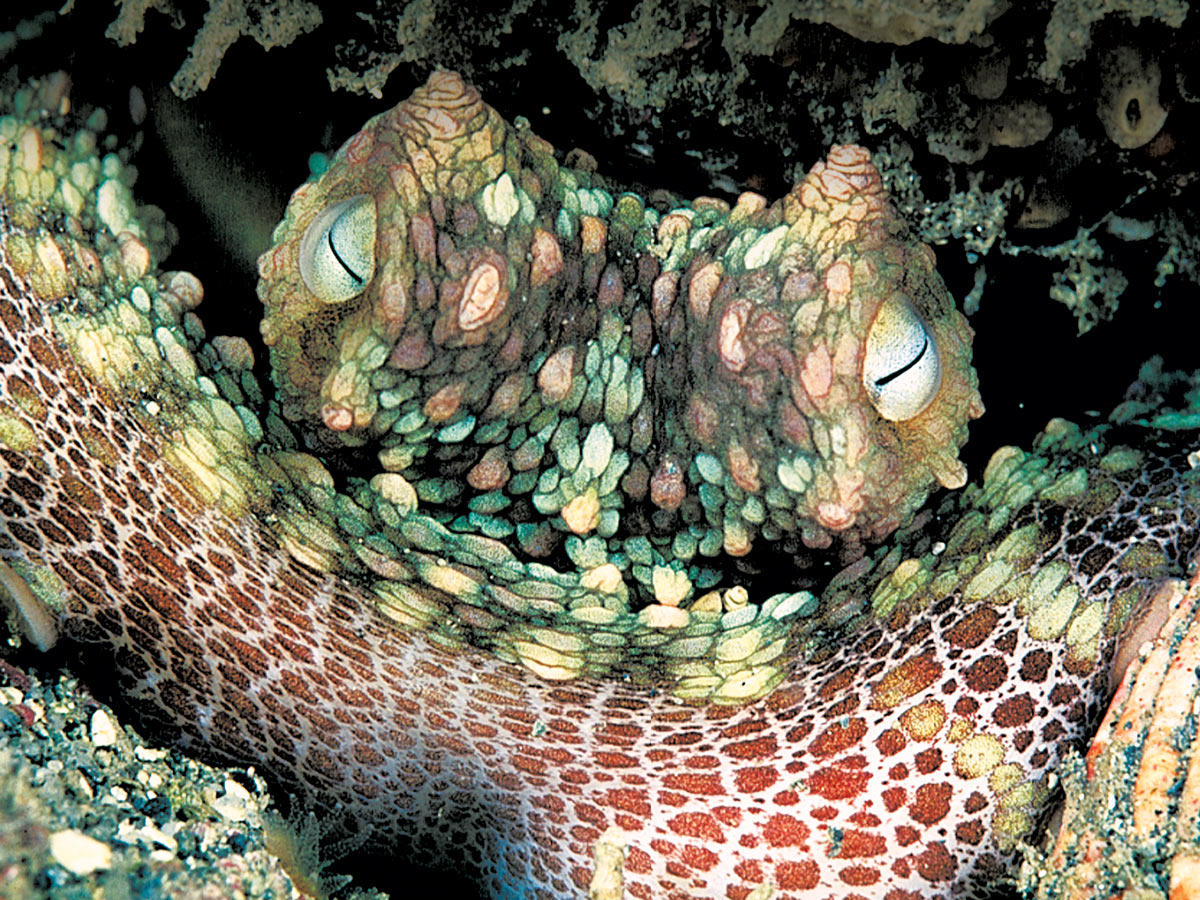

As I would approach, his eyes would dilate, and the texture and color of his skin would change. Excited to see me? Probably not, but it entertained me to think he might recognize me.

After a couple of dives I moved in closer trying to get a better angle. This was when I spotted the eggs. It turns out, “he” was a female. And a mama. No wonder she was staying put.

I continued to check on her for a few more weeks, and then one day she and the eggs weren’t there.

Kim and I continued to look for octopuses, hoping for more special encounters but while none would match Spot, other extraordinary encounters would follow.

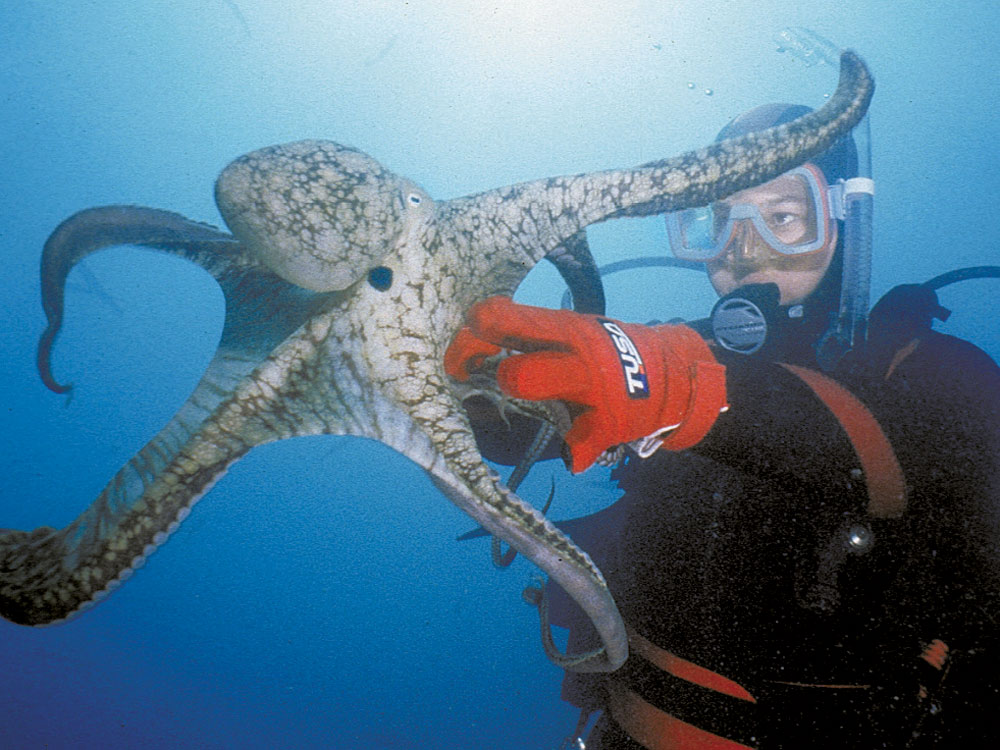

Under the Newport Pier a small curious octopus crawled up on my hand. On another beach dive at Gladstone’s in Malibu an exceptionally large octopus climbed onto Kim. It decided to explore her regulator and mask a bit too aggressively, so she had to gently push it away.

As exciting as these encounters are, they are rare. Octopuses can be curious but most of the time they are very shy.

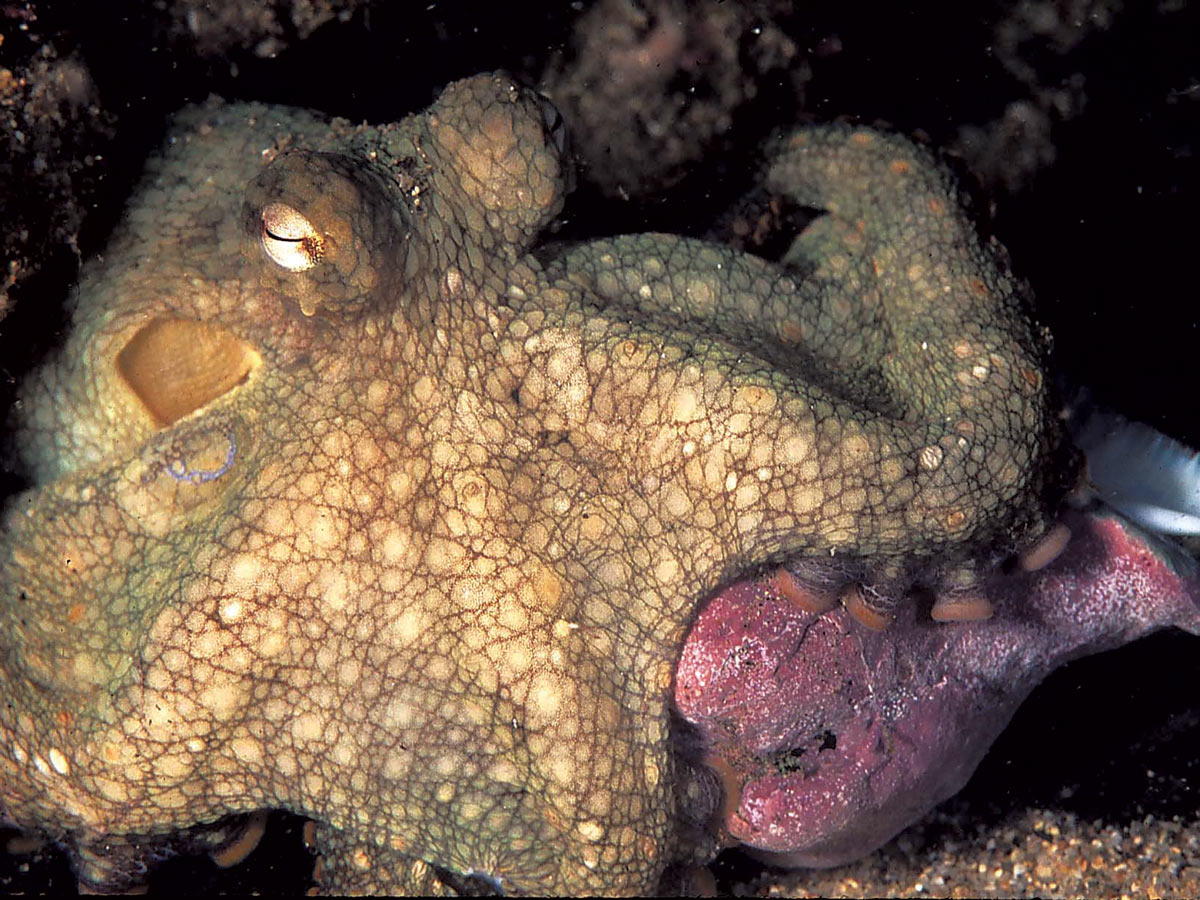

Using tiny organs in its skin known as chromatophores the octopus can change its pigment in a flash for camouflage and to express moods. Eye pupils also indicate its level of excitement. Photo by Dale and Kim Sheckler.

How to Up your Octo Odds

Octopuses are more common on California reefs than one might think but because they are masters of camouflage it’s likely you’ve swam right past them on your dives. If you want to see them, move slowly, and look for the clues.

Perhaps the best way to find an octopus is to find its den where it hides out of sight most of the day. Just like Spot they venture forth to gather food they will often drag back to their dens to feed on at their leisure. Some of their more common foods are crabs and small fish but they also enjoy small clams. It is the empty clam and mussel shells that are the best clue to the den whereabouts.

As you cruise across and around reef edges look for small pockets and crevices with an unusual amount of clam shells scattered about. Peek inside the small dark hole and you stand a pretty good chance of seeing an octopus. They simply cast off the empty shells into their trash heap, which is also known as a “midden.” In addition, they like to pile up other empty shells for added protection at the entrance to their den.

Here are a few tips to try if you find an octopus in its den.

First, approach low and slow. Like many ocean creatures they are sensitive to sudden movements. You will also find them sensitive to your breathing, not that you can do much about that (unless you are free-diving or using a rebreather) but you can breathe rhythmically, slow and steady. Relax. They are remarkably intelligent and can probably sense your state of mind. You can use the rumble of your bubbles to your advantage. Predators simply don’t make a lot of noise like we do. We announce our approach. Even so, don’t pounce on them. Slow down.

As you draw close, pay attention to the dilation of their pupils. They will fluctuate with your movements, contact with the reef and their midden which is part of their home territory. If you are carrying a camera, be careful not to bump into anything. Notice that the octo’s pupils will likely fluctuate with your breathing. It is interesting to watch and makes for good video if you can draw in for an up-close and personal macro image. Be patient. It takes time to develop the trust.

If you can get low enough look up at the roof of the crevice and you might spot some eggs. This indicates a nesting female. This will assure you the female will not flee but will hunker down even closer to protect her brood of eggs.

Females will not eat when guarding their eggs. In fact, they slowly starve to death as they tend to their clutch.

While you can occasionally see octopus out in the open any time of day, your best bet is at dusk and dawn. What you do when you find an octopus out in the open will have a lot to do with the quality of your encounter.

Nine times out of ten they will squirt a cloud of ink and swim away, but sometimes they are curious and will allow you to approach. Always let the octopus be in charge of the encounter. Don’t chase. Don’t ever grab at them. Grabbing them will cause their slimy outer coat to slough off and can damage their skin or expose it to infection. They may even detach an arm while attempting to flee your grasp.

If the octopus wishes to make contact with you, lucky you! Just remain still and enjoy the encounter.

Octopus are a favorite food of the bottom-dwelling cabezon. Photo by Dale and Kim Sheckler.

They’re Smart Suckers

The octopus’s arms are quite unique. Each sucker on each arm can taste. If it somehow loses an arm, it grows back. In addition, each arm has its own mini-brain and is able to act independently. Yes, the octopus has nine brains, one in each of its eight arms and the larger main brain that brings it all together. Its main brain is circular in shape surrounding its mouth.

Octopuses are remarkably intelligent. It is said that they are as intelligent as a house cat, but I would not want to insult the octopus (I am not a cat person). It is by far the smartest of all the invertebrates. The octopus can solve complex problems and can navigate a maze with ease. Research has even shown they exhibit a pattern of “play” behavior. It can even recognize individual humans. One report from a German aquarium showed it learned how to turn out the lights by short-circuiting them with a squirt of its siphon!

Not only does it have multiple brains it also has more than just one heart. One circulates blood to its entire body and the other two work with its two sets of gills for providing oxygen to the blood. Its blood is blue, as it is rich in copper.

Predator and Prey

Another little-known fact is that all octopuses are venomous but the only one deadly to humans is the blue-ring octopus that lives in the tropical Pacific. If your dive travels lead you to the South Pacific, do not ever handle a blue-ring octopus, as its neurotoxin is 10 times more deadly than cyanide.

The ink of some octopuses is also toxic but is no threat to humans. Not only does the ink disorientate the prey, but toxins in the ink can temporarily blind and even partially paralyze its stalker.

Its best defense is the octopus’s ability to blend in with its surroundings. Its camouflaging ability is remarkable enough to fool even an experienced diver. In a flash, the octopus can change its color and skin texture to match the bottom substrate including rocks and sand. It can shift its coloration and texture so quickly that as it moves, its looks like a moving rock.

Avoidance of predators is key as they have a lot of them. In addition to seals, they are hunted by a variety of bottom fishes including the cabezon (another master of camouflage) and the moray eel.

Moray eels, lobster and octopus form a strange triangle of predator and prey. A favorite meal of the octopus is the California spiny lobster. A food of the moray is the octopus. You often see lobster in the same holes with morays. The lobster receives a quasi-protection from the octopus from the moray and the eel benefits using the lobster as “bait” to draw the octopus for a strike.

Octopuses are agile hunters as well. With their soft pliable bodies and no bones to hold them back, even larger specimens can slip through the tiniest holes.

Let me introduce you to my friend Spot. Photo by Dale and Kim Sheckler.

Courtship and Reproduction

The mating and reproduction process in octopuses is also remarkable. A pair will communicate with a flash of colors, patterns and textures. Embracing and wresting then ensues. Once the female accepts the male as her partner, the male octopus uses a specialized arm to transfer sperm packets to the female’s mantle.

Once the mating is complete, the male had better flee quickly, as female octopuses are known to strangle males to death and then devour them. Not a very romantic ending, really. Slinking back to its den the female attaches the now fertilized eggs to the roof of its hole and aerates them with gentle puff from its syphon for 2 to 4 months. As previously mentioned, she does not eat during this time, and will slowly starve to death as she tends the eggs.

When the tiny baby octopuses burst from their egg sacks, they drift along the currents before settling to the seafloor, feeding on tiny crustaceans, and becoming part of the food chain themselves. It is estimated that of the typical brood of the octopus’s tens of thousands of eggs only a few will survive to adulthood.

This octopus became a little too inquisitive for Kim. She had to pushed it away. Photo by Dale and Kim Sheckler.

California Octos

The most common species found in California waters are the two-spotted octopus (hence the originality of my name of my friend “Spot”). Two distinctive spots under the eyes make this one easy to identify. They average about 24 inches in length from the end of its body to the tip of its arms. They tend to hang out more in the southern part of the State.

The other octopus common to California is the smaller red octopus. They average about 16 inches although those encountered by divers are usually much smaller. Divers sometimes see them holed up in human trash debris in submarine canyons.

The giant Pacific octopus is present in the northern sections but rarely seen by California divers. They are more common in the Pacific Northwest. They average a whopping 132 pounds and larger specimens can reach several hundred pounds. These behemoths are not dangerous to humans, but some foolish divers have nearly drown trying to wrestle them.

So, how is it going to go with your encounter with much smaller octopus species common to California? That depends on your approach. Much like our encounter with Spot, if you are patient, there’s a good chance you can have your very own intimate meeting with one of these intelligent and curious creatures.