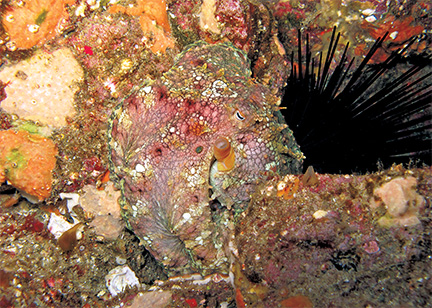

While two-spot octopuses are not uncommon in Southern California waters, they aren’t always easy to spot. They are usually wedged into a crevice. Thus, when I came across one sitting quietly on top of a ledge, I took a photo. I expected the animal to flee when my strobe flashed but it did not. I took another photo and ventured closer. That’s when I noticed there were two octopuses, so well camouflaged they blended into the substrate.

While two-spot octopuses are not uncommon in Southern California waters, they aren’t always easy to spot. They are usually wedged into a crevice. Thus, when I came across one sitting quietly on top of a ledge, I took a photo. I expected the animal to flee when my strobe flashed but it did not. I took another photo and ventured closer. That’s when I noticed there were two octopuses, so well camouflaged they blended into the substrate.

The cephalopods were about eight inches apart, linked by an arm that extended from one to the other. They were pseudocopulating: the male had inserted his hectocotylus arm into the female’s mantle cavity and was transferring a sperm packet to her. Two-spot octopuses are solitary animals and even during mating these two creatures (and others of their species I have photographed) seemed loathe to be close to each other. After two more photos, I left. The octopuses took no notice of my departure; they remained as immobile as the rocks around them.

Later, when the female laid her eggs (there could be tens of thousands of them), the sperm packet would rupture and fertilize them. Female two-spots tend their eggs 24/7, aerating and cleaning them until they hatch, which can take two to four months. They don’t eat while brooding and die just before or when the eggs hatch. The males don’t have long lives, either, living only two to three years, about the same as the females.

The eggs in the photo shown here were laid by a female two-spot in an aquarium and I don’t know if they were fertilized. The female appeared near death when I saw her. The green stuff on the walls of the aquarium is algae.

The class cephalopoda includes octopuses, squids, cuttlefishes and nautiluses (also called argonauts). The word means “head foot” and refers to the fact that the head is located between the foot and the body mass rather than being separated from the foot by the body mass. Cephalopods belong to the phylum mollusca, which also includes gastropods (snails and nudibranchs), bivalves (scallops and clams) and polyplacophora (chitons).

Three of the most common octopus West Coast divers may encounter include: Two-spots, found from Santa Barbara to Baja; red octopuses, found from Alaska to Baja; and giant Pacific octopuses, found from northern Asia to California.

The only octopus species I have photographed in California waters is the two-spot, which can reach lengths of 24 inches, including the arms. The name comes from the blue spot found on each side of the head below the eye and you can see one on the octopus photographed out in the open. The photo was taken off San Clemente Island last August. The octopus wasn’t very big and I only saw it because it was in motion. It soon settled down and ignored me and my camera. The photo reveals the many colors and textures of the creature’s skin as well as that some of its eight arms are tucked into a crevice and are probably clutching prey. Octopuses eat mollusks and crustaceans as well as small fish, all of which are first paralyzed with toxic saliva. The beak, similar to that of a parrot, can perforate shells and break bones. A radula (a rasp-like structure of tiny teeth) scrapes out the edible parts of shelled prey. The diet of baby two-spots (tiny miniatures of their parents when they hatch) includes amphipods or mysid shrimp.

Two-spots have plenty of predators; they are on the dinner menus of moray eels, big fish and sea lions. Octopus defense includes being able to release a cloud of ink, inflict injury with their beaks and use the powerful grip provided by the suckers on their arms. The suckers also contain thousands of taste receptors and millions of texture receptors. Much like starfish arms, octopus arms can be shed during a struggle with a predator. Also like starfish arms, they will be regenerated.

Octopus are fascinating to watch when they are in motion. They use their arms and suckers to crawl along the bottom and bursts of water from their siphon to jet along just above it, changing shapes and colors as they go.

The octopus tucked into a crevice (which may or may not be its den) is exhibiting normal coloration. The ability to change color is complicated and involves three skin structures: chromatophores, iridophores and leucophores. Chromatophores are the color organs while the reflective iridophores act like mirrors or prisms. Also reflective, leucophores help match the color of the octopus to its background, while the animal’s brain controls the color patterns.

Cephalopod eyes have a cornea, iris, lens and retina that are similar to vertebrate eyes. According to The Living Bay, “As so often among animals, exceptional vision goes with uncommon intelligence. Cephalopods…whose optic lobes are much larger than the rest of their brain…can be quickly conditioned to respond to geometric patterns such as triangles and squares, they can learn to imitate the behavior of others and they have excellent long-term memory. They have a half billion nerve cells, one-third of them in the brain — more than any other invertebrate….”

The author wishes to thank Genny and Shane Anderson for assistance with this article.

Two-Spot Octopus Stats

Octopus bimaculatus or bimaculoides

Phylum: Mollusca

Class: Cephalopoda

Subclass: Coleoidea

Superorder: Octopuspodiformes

Order: Octopuspoda

Suborder: Incirrata

Superfamily: Octopuspodoidea

Family: Octopuspodidae

Genus: Octopus