Eighty years after it was deployed during the last half of World War II as a lifesaver for troops and civilians plagued by malaria and typhus, DDT is still in the news. Powerful images of decaying barrels filled with DDT and other toxic waste have been photographed by underwater robots on Southern California’s coastal shelf. And top-notch investigative environmental reporting by the Los Angeles Times is helping researchers, officials and the public get a better picture of the long-term effects of historic dumping of DDT and other industrial waste up and down the coast.

Robots are playing other key roles in shedding light in dark places, after being deployed to survey a toxic waste dumpsite in high definition 3,000 feet (900 meters) below the surface. Robots also collected sediment and biological samples adjacent to six sunken barrels. The robots, autonomous underwater vehicles (AUVs), were deployed by a team of researchers from the Scripps Institution of Oceanography in partnership with NOAA.

The dumpsite surveyed is roughly 12 miles offshore of Los Angeles (the Palos Verde Peninsula) and eight miles from Catalina Island, both prime locations for recreational diving, boating and fishing.

Scientists have documented DDT in seafloor sediments, fish, birds, and marine mammals, including dolphins and sea lions, indicating that DDT moves from sediment and its communities into the water column food web. Exposure to legacy pesticides such as DDT, in tandem with a viral herpes infection, exposes sea lions to an aggressive urogenital cancer, according to a new study published in Frontiers in Marine Science. Synergism between viral infection and exposure to toxic chemicals increases cancer development odds. Additionally, brown pelicans are laying eggs with thin eggshells that are leading to the death of their chicks.

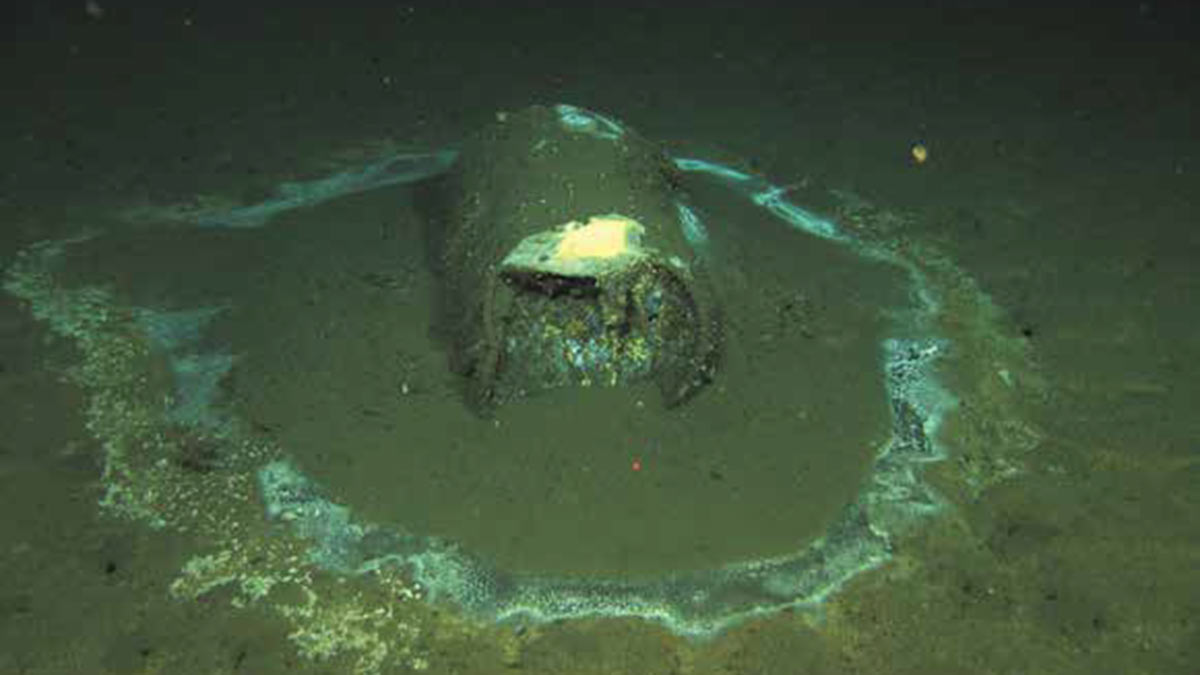

A barrel of DDT found off the coast of Santa Catalina Island at a historical dumpsite between the Palos Verde Peninsula and Catalina. Credit: David Valentine, UC Santa Barbara/RV Jason

The Dirt on DDT

Dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane, DDT for short, is a tasteless, colorless and near odorless synthetic crystalline chemical compound originally developed as an insecticide. Because DDT is very stable it tends to persist in the environment, becoming concentrated in animals at the head of the food chain. DDT became infamous for its destructive environmental impact and its use is now banned in many countries.

Deep and Widespread Dumping of DDT

The tip of the DDT iceberg surfaced into public view in 2011 and 2013 when UC Santa Barbara professor David Valentine documented concentrated accumulations of DDT in seafloor sediments, and visually confirmed with underwater images decaying barrels on the seafloor.

In March 2021, an expedition led by the Scripps Institution of Oceanography, in collaboration with NOAA’s Office of Marine and Aviation Operations and the National Oceanographic Partnership Program, mapped more than 36,000 acres of the seafloor of the San Pedro Basin, in a region found previously to contain high levels of DDT. Two robotic AUVs, the REMUS 6000, capable of depths up to 19,600 feet (6,000 meters), and the Bluefin, capable of depths up to 4,900 feet (1,500 meters), were deployed in tandem to map the seabed floor at a high resolution.

The survey, conducted onboard the Research Vessel Sally Ride, identified more than 27,000 possible barrels, and a total of more than 100,000 debris objects. “Unfortunately, the basin offshore Los Angeles has been a dumping ground for industrial waste for several decades, beginning in the 1930s,’’ said Eric Terrill, chief scientist of the expedition and director of the Marine Physical Laboratory at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography. “Now that we’ve mapped this area at very high resolution, we are hopeful the data will inform the development of strategies to address potential impacts from the dumping.” The expedition team included 31 scientists, engineers and crew conducting around-the-clock operations.

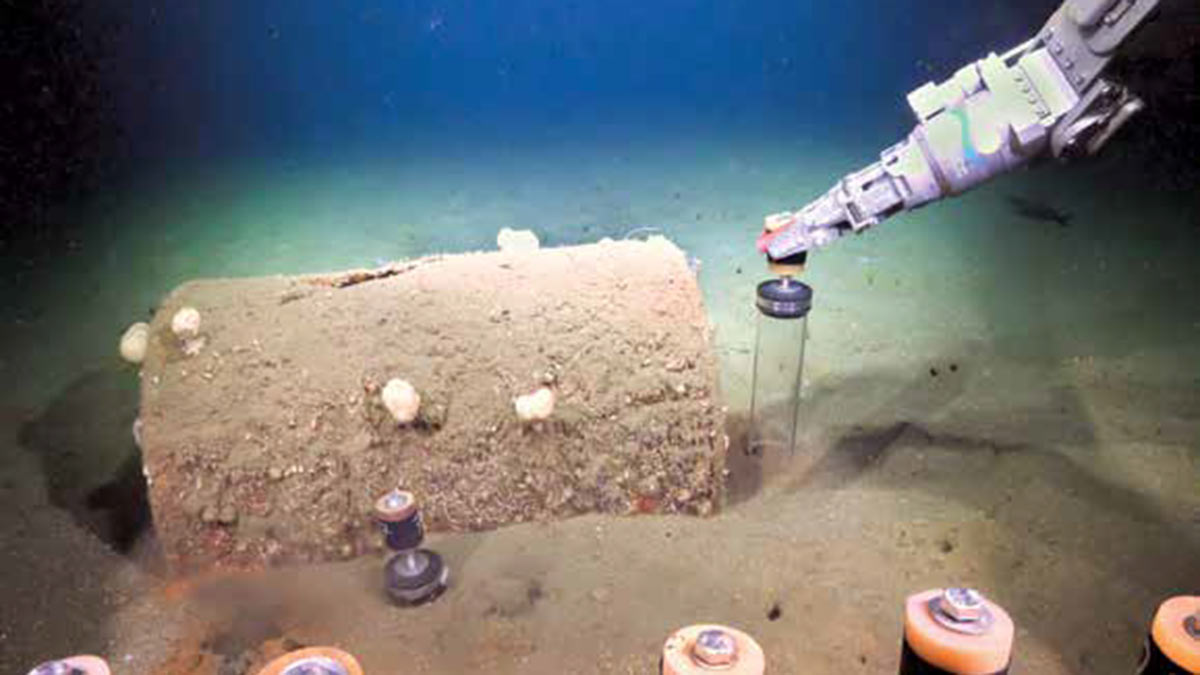

In August 2021, during another Scripps expedition aboard the Schmidt Ocean Institute’s R/V Falkor, researchers assessed the biodiversity in an area rich in minerals that are of interest to deep sea mining engineers, and also explored the DDT dumpsite with robots, collecting sediment and biological samples around six barrels to assess the potential ecological effects of the dumpsite and to determine the level of DDT in the ecosystem.

Researchers use Remotely Operated Vehicle (ROV) SuBastian to collect sediment push cores and record video footage, data that will be used to add to the assessment on how this stretch of deep sea is responding to DDT. The science team is conducting research on the DDT dumpsite off the coast of Los Angeles where barrels of chemicals were dumped from 1947 to 1982. Credit: Schmidt Ocean Institute.

Record Contamination Levels

The deep ocean basins off the coast of Los Angeles have long been historical dumpsites for DDT and other hazardous industrial waste. The Montrose Chemical Corporation of California was the largest producer of DDT in the US, from 1947 until it stopped production in 1982. Improper disposal of chemical waste from DDT production resulted in serious environmental damage to the Pacific Ocean near Los Angeles. The former main plant, near Torrance, was designated as a Superfund cleanup site by the EPA. A $140-million Superfund battle in the 1990s exposed decades of environmental abuses, including disposing of toxic waste through sewer pipes that poured directly into the sea, and deploying waste haulers to ocean dumpsites.

Investigative reporting by the Los Angeles Times documented shipping logs from a disposal company associated with Montrose Chemical, showing that 2,000 barrels of DDT sludge could have been dumped each month from 1947 to 1961 into a designated dumpsite. Logs show that many other industrial companies in SoCal used ocean dumping grounds.

In 1972 the Marine Protection, Research and Sanctuaries Act of 1972 (the Ocean Dumping Act), became law. Despite the ban, DDT and other toxic waste production continued for the next decade, and it was common practice to dispose of industrial waste off the coast.

In March 2021, Sen. Dianne Feinstein, DCalif., wrote to the Environmental Protection Agency requesting urgent action to clean up coastal California. “Some areas off Catalina Island have recorded concentrations of DDT at rates 40 times higher than the highest level of contamination at Palos Verde.”

On August 5th of this year, in internal memos just made public, the EPA said that industrial waste, including DDT, was not contained in hundreds of thousands of sealed barrels dumped in coastal waters, and that the scope of the damage is more devastating than initially thought. Old shipping logs show that thousands of barrels of DDT and other chemicals could have been dumped in coastal waters.

Based on newly discovered information in shipping records, much of the waste was not in barrels, instead being dumped directly into the ocean from tank barges. According to reporter Rosanna Xia of the Los Angeles Times, the word “barrel” was used as a unit of volume rather than meaning an actual container. Records revealed that other chemicals and millions of tons of oil-drilling waste were also dumped decades ago in more than a dozen areas off the coast. As many as half a million barrels of DDT waste have not been accounted for, based on searches of old records.

“That’s pretty jaw-dropping in terms of the volume and quantities of various contaminants that were dispersed in the ocean,” says John Chestnutt, a Superfund section manager leading the EPA’s technical team during the investigation. “This also begs the question: So, what’s in the barrels? There’s still so much we don’t know.”

Research Vessel Sally Ride off the Scripps Pier, La Jolla.

Photo by Erik Jepsen/UC San Diego.

Funding and Fact-Finding

On March 14 of this year UC San Diego received $5.6 million in federal Community Project Funding for monitoring and research for Southern California DDT dumpsites. The funding was approved by Congress at the request of Sen. Feinstein. Governor Gavin Newsom just matched the federal funding with another $5.6 million in state funds.

The new funding will be used to analyze the 2021 samples and to conduct expanded surveys of dumpsites to assess the condition of waste containment barrels and to support data collection. Scripps scientists also plan on assessing fisheries and ecosystems by measuring the toxin levels in preserved marine animals in the Scripps collection, dating back to the 1930s, prior to known dumping. Previous research indicates that the contaminants at the dumpsites have a distinct chemical fingerprint that can be traced into the food web, including into marine mammals.

More Questions Than Answers

Scripps chemical oceanographer and professor of geosciences Lihini Aluwihare coauthored a 2014 study that found a high levels of DDT and other man-made chemicals in the blubber of bottlenose dolphins that died of natural causes. “The uniquely high burden of DDT in top predators feeding in Southern California waters has been known for some time. The extent of the dumping ground helps to explain some of these observations,” said Aluwihare.

“These results,” she adds, “also raise questions about the continued exposure and potential impacts on marine mammal health, especially in light of how DDT has been shown to have multi-generational impacts in humans. How this vast quantity of DDT in sediments has been transformed by seafloor communities over time, and the pathways by which DDT and its degraded products enter the water column food web are questions that remain to be explored.”

DDT Timeline

- 1874 First synthesized by an Austrian chemist.

- 1939 Swiss chemist Paul Hermann Müller discovers DDT’s insecticidal actions.

- 1942 DDT is used in the second half of World War II to limit the spread of malaria and typhus among troops and civilians. Both diseases are spread by insects.

- 1945 DDT becomes available for public sale in the US as an agricultural and household pesticide. Concern is already being expressed about the chemical. Agricultural use becomes widespread, helping to protect crops and livestock from insects.

- 1948 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine presented to Müller “for his discovery of the high efficiency of DDT as a contact poison against several arthropods.”

- 1962 Opposition to DDT gains momentum with the publication of Rachel Carson’s seminal environmental book, Silent Spring.

- 1972 Public outcry about the dangers of DDT to the environment, people and animals leads to a ban on the agricultural use of DDT in the US when the Marine Protection, Research and Sanctuaries Act of 1972, also called the Ocean Dumping Act, is enacted.

- 1973 Along with the US ban on DDT, the Endangered Species Act of 1973 is a major factor in the comeback of the US national bird, the bald eagle, and the stops the near extinction of the peregrine falcon.

- 2004 A worldwide ban on agricultural use of DDT is formalized by the Stockholm Convention on Persistent Organic Pollutants.

- 2005 DDT is routinely detected in almost all human blood samples. There has been a drastic decline in amounts of DDT in human blood since. Despite the ban, DDT is still regularly detected in food sampling conducted by the USDA.

- 2022 DDT still has limited use in disease vector control for malarial infection, although this use is controversial due to environmental and health concerns. Malaria remains the primary public health issue in many countries.

Legacy Pesticides in Fish and Shellfish

Legacy pesticides such as DDT persist in the environment and can accumulate in fish and shellfish. Women can pass legacy pesticides on to their babies when pregnant and breastfeeding. Legacy pesticides can affect the developing fetus, resulting in possible learning and behavioral problems; potential effects on reproduction and decreased fertility; and increased cancer risk. Here are recommendations for reducing your risk of consuming legacy pesticides in fish or shellfish:

- If you catch your own fish, follow the OEHHA fish advisories for California water bodies at oehha.ca.gov

- If legacy pesticides are present at higher levels in certain bodies of water, avoid fatty fish, bottom feeders, fish that eat other fish, and larger older fish.

- If fish are from low-contaminate areas, keep in mind that legacy pesticides accumulate in the skin, fat and some internal organs of fish and shellfish.

- Trim the fat, remove the skin, and fillet the fish before cooking. Eat only the skinless fillet.

- For crab and lobster, remove the internal organs “(guts,” “butter,” or “tomalley”) and rinse out the body cavity before cooking.

- Bake or grill fish in a way that lets the juices drain away. Throw away the cooking juices.

- Boil or steam crab and lobster and discard the cooking liquid.

- Do not use the fat, skin, organs, juices or the whole fish in soups or stews.