Red Algae Stats

Kingdom: Plantae

Class: Florideophyceae

Subclass: Corallinophycidae

(Calliarthron cheilosporioides)

Rhodymeniophycidae

(Gloiocladia laciniata)

Order: Corallinales

(Calliarthron cheilosporioides)

Rhodymeniales (Gloiocladia laciniata)

Family: Corallinaceae

(Calliarthron cheilosporioides) Faucheaceae (Gloiocladia laciniata)

Brown AlgaeStats

Kingdom: Chromista

Infrakingdom: Heterokonta

Class: Phaeophyceae

Order: Dictyotales (Dictyota coriacea)

Fucales (Sargassum muticum)

Family: Dictyotaceae (Dictyota coriacea)

Sargassaceae (Sargassum muticum)

Editor’s note: This is the first of a two-part installment on marine algae.

Writing and taking photos for this column has been a journey of discovery and enlightenment. I had learned the common names of many marine creatures I encountered (most specifically in SoCal, where I have spent the most time) but didn’t delve into anything bordering on the scientific. I also photographed a lot of “stuff” I couldn’t identify. While looking for material for this column, I’ve made a lot of progress on that.

The Internet is a godsend, but, this article proved more difficult to research than most. Sometimes the specimens I compared mine to were photographed out of the water and identified by lab work — and all of my photos were shot underwater. I quickly discovered that while some marine life looks pretty much the same in or out of the water, most algae do not!

According to an article in the LA Times, there are more than 300,000 identified species of algae and, “Many top dermatologists agree that seaweed is an extremely effective skin care ingredient, full of antioxidants, minerals and amino acids.” The seaweed mentioned in the article, Undaria pinnatifida, is native to Asia but has spread to almost every continent. According to Dr. Kathy Ann Miller of UC Berkeley, it is even found in most SoCal harbors.

Algae are classified as red, brown or green based on the color of their photosynthetic pigments and their evolutionary lineage. They all have chlorophyll a but only green algae look green. Other pigments mask green chlorophyll a in brown and red algae.

Red and green algae are currently considered members of the Kingdom Plantae, while brown algae (including giant kelp) are currently considered members of the Kingdom Chromista, which means, “colored.” With the help of Drs. Miller and Dan Reed of UC Santa Barbara, I have confirmed the identity of 12 algae and plan to write at least two articles on them. This first article discusses four common algae; two red and two brown. One of the browns is an invasive species.

Marine Algae

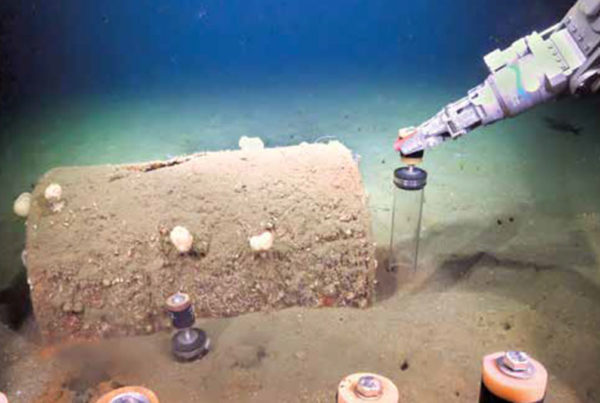

Marine algae are unlike their terrestrial cousins. Instead of roots, they have holdfasts that attach them to rocks and other hard substrates. Some holdfasts bear a superficial resemblance to roots while others are disk shaped. Algae don’t have leaves or stems though they have blades and stipes that look like them. Algae also lack water and food conducting structures because their body (called a thallus) absorbs nutrients right from the water. Most algae also use sunlight to synthesize carbohydrates from carbon dioxide and water. While topside plants develop from an embryo inside a seed or fruit, reproduction in algae can be quite complicated. Stay tuned, I will attempt to explain it in the next article!

Descriptions of the four algae chosen for this article follow.

Coralline algae (Calliarthron cheilosporioides): This red alga, common in SoCal kelp beds, has an encrusting base and articulated branches that can be more than nine inches long. Because the calcified branches are stonelike, articulated coralline algae have few predators. Although the species pictured here has flat, chainlike branches, other species vary in form and some look more like feathers. Species of coralline seaweeds can live 50 years and range from Alaska to Baja.

Species of encrusting coralline algae lack the upright branches and are extremely common on many rock surfaces. They have been said to resemble “dried Pepto Bismol.” Nonetheless, they provide a colorful background for images of other marine life and are very important ecologically.

Gloiocladia laciniata (formerly Fauchea laciniata): A widespread red alga, Gloiocladia laciniata has no common name. The thallus of this small, low growing (one to five inches tall) seaweed is red but appears iridescent blue underwater. According to The Living Bay: “this color results from the interference of light waves reflected from very thin, actually colorless layers in the alga’s cell walls.” When removed from the water the cell walls dry out, stop scattering light and the plant’s red color is revealed. Gloiocladia laciniata is found from Alaska to Baja, in intertidal waters to depths of 75 feet.

Dictyota coriacae (formerly Pachydictyon coriaceum): This common alga doesn’t have a common name. Dense masses of it are found in the often-surgy shallows on the frontside of San Clemente Island, where the water is relatively warm and usually sunlit. Although it is a brown alga, it appears green in my photos. The tips of the blades are forked and one side is usually longer than the other, forming “mittens.” Dictyota coriacae is able to reproduce asexually from fragments, which is why it does well in near shore waters with surge, which can shred seaweed.

Japanese Wire Weed: Sargassum muticum: This brown alga is an invasive species from Asia that was probably introduced to British Columbia waters in the 1930s and quickly spread south. Paradoxically, as it becomes more common in our waters, where it competes for sunlight, space and nutrients with giant kelp and other native algae, it is disappearing in its original habitat, causing concern. Native species there depend on it. Here it is a pest, without natural predators until it begins to die, when the invertebrates that live on it are exposed and eaten. The photo here was taken off Santa Barbara Island several years ago.

Wire weed has been found in SoCal waters since 1970 and, according to Dr. Bill Bushing, thrives during years with warm water, which kills giant kelp. It is currently found from Alaska to Baja.

It should be noted that the tropical floating species of Sargassum host many different marine organisms, offering food and shelter.