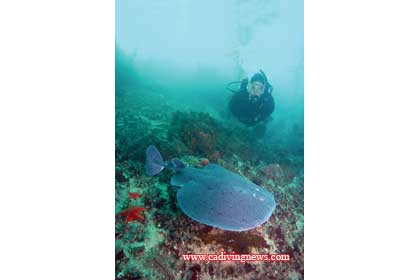

Last August, a Pacific electric ray sought out the company of divers on more than one dive on Farnsworth Bank’s high spot. While this didn’t happen to me, it did to several people on my trip. They had photos and video of the ray hovering a few feet away from a diver in a relaxed and nonaggressive way.

While doing internet research in November, I found another report of a ray/diver encounter at Farnsworth that took place several months after my trip.

This behavior is extraordinary for a couple of reasons, the first being that electric rays are nocturnal and the encounters took place during the day. Also, while electric rays aren’t afraid of divers and may come close to check us out, they aren’t known to stick around or make repeat appearances.

My own up-close experience with an electric ray in 1979 was startling, to say the least. I was gradually descending in midwinter off San Clemente Island, looking for likely lobster lairs, when I received a powerful jolt that ran from my right hand to my shoulder. I had no idea what had happened and immediately began to ascend. That’s when I saw a ray just above me. The ray swam off. I floated on the surface for several minutes, processing what had happened. When I realized I had been shocked by an electric ray, not stung by a bat ray, I continued my dive. My arm tingled for quite awhile. Indeed, every time I thought of the incident for years afterward I would feel the jolt.

I have no idea why the ray zapped me. Did I bump into it? The visibility was excellent but my attention was focused on the bottom. Electric rays are gray or bluish gray on top and can blend into the water. They are easiest to see from below because their undersides are white.

The scientific name for the Pacific electric ray is Torpedo californica. In his book, Probably More than You Want to Know About Fishes of the Pacific Coast, Dr. Milton Love points out: “torpedo is Greek for numbness.” According to A Living Bay: “The ray’s electric organs are in its greatly enlarged pectoral fins, and they occupy almost a quarter of the ray’s body mass.”

Big Pacific electric rays are capable of delivering an 80-volt shock (researchers have measured this). According Reef Fish Identification: Florida, Caribbean, Bahamas, the Atlantic torpedo ray (Torpedo nobiliana) can deliver up to a 220 volt shock and the lesser electric ray (Narcine Brasiliensis), a 14 to 37 volt shock. Neither of these latter two rays is found in California waters.

The ability to shock is not primarily a defensive weapon; it simply allows electric rays to immobilize their prey so it can be eaten. Sharks and Rays of the Pacific Coast notes: “An electric ray’s energy sources are limited. It uses up most of its shocking power on the first jolt and must rest and recharge after each attack.”

Pacific electric rays can be nearly five feet long and are found from British Columbia to Baja California, in depths from 10 to 900 feet. The creatures usually spend the day lying on the bottom, covered with sand. Instead of swimming by using their broad, flat pectoral fins like wings, electric rays move their tails from side to side.

If an electric ray favors you with a visit, enjoy the encounter — but don’t get too close!