Pioneering. Trailblazing. Iconic. Legendary. These aren’t easy adjectives to live up to, but by all accounts, the diving industry’s Chuck Nicklin made it look easy. He did so with his trademark smile and an uncanny ability to sleep soundly practically anywhere, including on a rocking boat in a big storm.

Charles Richardson Nicklin, Jr. was born September 4, 1927, near Worcester, Massachusetts, and moved to the San Diego area in 1942 at the age of 14. He died at his La Jolla home on December 7, 2022, at the age of 95. His life was spent in, on, and under the sea. All over the world.

I got to know Chuck when we worked together to publish his book, Camera Man: Stories of My Life and Adventures as an Underwater Filmmaker. Although the book is fewer than 300 pages in length, the adventures Chuck enjoyed as a diver and freediver, spearfisher, dive shop owner, explorer and filmmaker could have filled volumes.

The news of Chuck’s death flooded social media sites with memorial tributes. In this article, you’ll learn of Chuck’s accomplishments as a diver, businessman, photographer and filmmaker, and so on. But what struck me the most when reading the social media posts was that Chuck is remembered not for his long list of accomplishments, but for being a genuinely nice guy. For his “California cool” vibe. For helping people, for making them welcome and included. For loaning his camera gear – or the keys to his Porsche. And for his perennial smile.

Diving and Filming

When a group of California’s early divers, including Conrad Limbaugh, Jim Stewart, Wheeler North and others, opened the San Diego Diving Locker in June 1959, they hired Chuck to run it. Under Chuck’s command, it became the area’s leading dive shop, the place where legions of divers were trained, and where acclaimed underwater photographers, including Howard Hall and Marty Snyderman, got their starts.

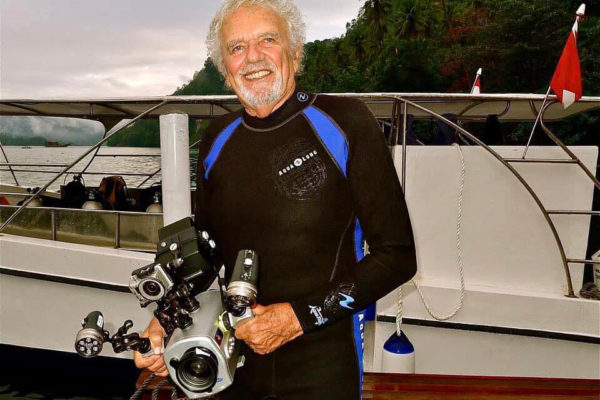

A champion spearfisher, Chuck started tinkering with crude underwater cameras in the late 1940s, and before long, he was even a better underwater photographer than he was a spearfisher.

Chuck co-founded the San Diego Underwater Photographic Society and started the San Diego UnderSea Film Exhibition, an annual film festival currently in its 24th year.

Whale “Riding”

In January 1963, Nicklin was headed out to the undersea canyons off La Jolla when he and his dive buddies spotted a Bryde’s whale entangled in a fishing net. Nicklin didn’t hesitate to jump in the water and help free the whale. While doing so, he climbed onto its back, sitting astride the whale. A friend captured the moment with a photo. And in that instant, Chuck Nicklin became “the man who rode a whale.”

The photo and an accompanying article appeared in the San Diego Union. Before long, the story ran in Time magazine. Next, Nicklin was invited to appear on the popular television program “To Tell the Truth.” And the folks at National Geographic, figuring he was a whale expert, hired him as an underwater photographer for a feature article.

A chance encounter with a whale opened doors. But it was Chuck’s charisma that filled the room. And fueled his success. It wasn’t long before he legitimized himself as the go-to guy for underwater photo and movie shoots. He quickly racked up credits as an underwater cameraman for blockbusters like “The Abyss,” “The Deep,” and two James Bond films, “For Your Eyes Only” and “Never Say Never Again.”

Fame and Family

Chuck’s travels took him away from his young sons Flip and Terry quite a lot, but when he was home, he had them out on the water with him. Both sons were fixtures at the Diving Locker, too. Flip went on to follow in Chuck’s footsteps and is also an acclaimed underwater photographer whose name appears on the NatGeo masthead.

As son Flip tells it, “I have been fortunate in life in having a father whose footsteps are great to follow, from Chuck’s Market in East San Diego to the Diving Locker in Pacific Beach, to traveling the world photographing, especially photographing whales. I grew up in a world hungry for adventure in the ocean. The first adventure with my father that I remember took place at La Jolla Cove, not surprisingly, as my family spent an amazing amount of time there. There was a rock offshore, ‘The Rock,’ shallow enough for people to stand on and, when the swell was right, maybe catch a body surfing wave. My father took me out to The Rock for the first time, hanging onto his shoulders and looking down at the marine world with my little green mask.

My brother Terry and I started working with my father at the Diving Locker before we were teenagers. The diving world was very different then. Family diving hadn’t really come along, and my dad was not yet a serious photographer or cinematographer. But he was a heck of a diver, and my model of what a diver should be.

Probably more important, he was great with people. Our dive shop was a haven for scientists, military divers, commercial divers, spear fishermen, and all kinds of characters in general. It served me well, this introduction to diversity, years later when I was traveling the world for National Geographic magazine.

Chuck got along with everyone. His success in diving, photography, and world travel is a result of that mix of skill and experience in the ocean and a personality that made people feel happy to be around him.”

In 1992, Chuck paired with his wife Rosalind Bailey Nicklin, with whom he shared many more adventures, including leading exotic dive trips and African safaris.

In The Deep with Chuck

By Howard Hall

I wrote the following chapter for Chuck Nicklin’s book, Cameraman. It’s a wonderful book filled with stories of the early days in underwater photography and filmmaking. Compared with Chuck’s history, I was a latecomer to this profession. In 1976, I was a wannabe. More specifically, I was a “I wannabe Chuck Nicklin.” To say that Chuck influenced my career path is simple understatement. Chuck inspired me to pursue this life, pointed me in the right direction, and gave me my first breaks. I will forever be in his debt.

In 1976 I was a 26-year-old diving instructor working in Chuck Nicklin’s San Diego Diving Locker. I was a moderately good spearfisherman and a budding underwater still photographer. Chuck had much to do with my initial pursuits in the latter. It is unlikely I would have achieved any significant measure of success as an underwater photographer without Chuck’s help and inspiration.

For example, in the back room of the Diving Locker, there was a small closet. Inside, Chuck kept his photographic equipment. Not only was this closet unlocked, but Chuck allowed his goofy assortment of snorkel salesmen to use his gear as they wished. Chuck’s only admonition was that the gear be returned to the closet in better condition than when it left. This was sometimes difficult to do. Loaning his precious camera gear to wannabes just becoming familiar with the functionality of o-rings was, of course, insane. But we worshiped him for it. I captured my first underwater images using Chuck’s Nikonos II camera. The first image I published in National Geographic was captured with a lens I borrowed from Chuck.

I was not the only wannabe that Chuck stimulated. There were many, and a significant number went on to stellar careers in diving and underwater imaging. Chuck’s lifestyle was narcotically inspirational. He owned the most successful dive shop in San Diego. He employed talented managers, so he didn’t seem to work very hard. He drove a Porsche. He had a new girlfriend every month – each more beautiful than the last. He married the last of these beauties, Rosalind Bailey, in 1992 and to whom he was devoted for the rest of his life. Chuck regularly traveled to far-off, exotic places as an underwater cameraman for hire. Chuck often warned his enraptured flock that underwater photography could not be considered a serious career. That without regular income from the Diving Locker he could not survive on camera assignments alone. That careers in banking, education, or retail management were much more mature. Then he would slip into his dark blue Porsche next to a stunning model and speed off to dinner at the Chart House. Banking! Seriously?

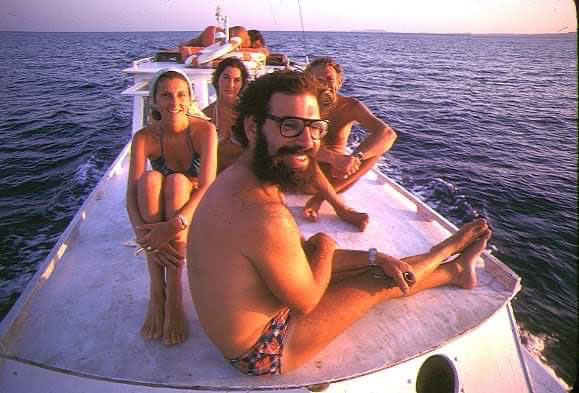

Chuck initiated my first major break in the underwater film business. He’d been hired to film underwater scenes for Peter Benchley’s motion picture, The Deep. A shark sequence was to be produced in the Coral Sea. The underwater film crew would be populated with diving luminaries including Al Giddings, Stan Waterman, Jack McKenney, and others. They needed a spearfisherman to help attract and incite sharks. I suspect prerequisites included experience with a speargun, unrealistic ambition, and no more than average IQ. Chuck asked me if I wanted the job. I considered the offer for less than a millisecond.

Months later, I was on a flight bound for Australia and took my seat tightly sandwiched between Stan Waterman and stuntman, Howard Curtis.

Eventually, we arrived in Townsville, Australia where we loaded up the first Australian liveaboard, Coralita, for the 30-hour crossing to the atolls of the Coral Sea.

For three weeks our crew filmed sharks in the Coral Sea. We had many memorable adventures during the expedition, but one of the dives we made in the Coral Sea was certainly memorable for both Chuck and me. It is the single time I ever witnessed what can only be described as a shark feeding frenzy.

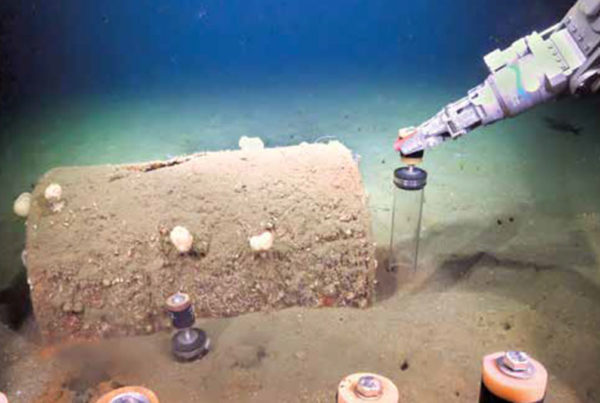

Our crew was on the bottom 110 feet below Coralita. Al had positioned a mock-up of a ship’s hatch cover and a suction dredge on the sand thirty feet from the edge of the reef. Doubling for Robert Shaw, Howard Curtis was to descend wearing a surface supplied Desco diving mask. Chunks of fish had been tied to the hose. Appropriately, Howard Curtis would not be relying on the surface-supplied air since we intended that sharks tear the hose apart. Instead, he would be connected to a pair of tanks via a twenty-foot low-pressure hose which we concealed beneath the sand once he reached the bottom. This part of the plan didn’t work out very well because sharks tore the hose apart only moments after Howard entered the water. Eventually, Howard did make it down carrying the pair of tanks under his arm.

The plan was quickly modified. Al, Stan, and Chuck would concentrate on sharks threatening Howard and would avoid shots of the severed hose above his head. With Howard standing on the hatch cover and the cameramen taking shelter against the coral reef, it was time for me to earn my pay. Al signaled to me by pointing his finger and cocking his thumb. “Shoot something,” was the signal. I was a bit reticent. Looking up, the water was filled with gray reef sharks.

Just beyond Howard Curtis and the dredge, there was a small clump of dead coral resting on the sand. Hovering above this limestone rock was a lovely little seaperch just over a foot long. I swam toward it rather hoping it would swim away. I realized that sixty or more sharks competing for one mortally injured little seaperch might produce a rather precarious situation. Hoping for a reprieve, I looked back over my shoulder at the film crew. Al gave the “shoot” signal again with an amplification that seemed to say, “What the hell’s the matter with you? Shoot, damn it. Shoot!” I took aim then looked up at the cloud of sharks one more time, giving the fish a final chance of escape. Then I fired.

The seaperch was impaled halfway up the spear shaft. I didn’t like the idea of it swimming to take shelter under my arm, so I shoved the gun away from me. Two feet from my hand, the spear gun was hit by three or more sharks and torn apart. A ball of sharks instantly formed and rumbled across the bottom creating a sound like an earthquake. Chuck, Al, and Stan rolled their cameras as Howard Curtis kicked at sharks that broke away from the roaring ball. I made it to the reef and hid behind Stan Waterman.

Once the action died down and the crew began their ascent, I swam out over the sand and retrieved the remains of my spear gun. Back aboard Coralita, Jack laid the pieces of the gun on the deck and began taking photographs of the remains. Chuck sidled up to me and said quietly, “You know Howard, no film is worth getting bit for.” This was not the sort of advice you take very seriously or consider very long before accepting. But I do remember those words. It was the sort of thing you remember when you are just starting out on a long journey. Chuck Nicklin was at the peak of his career. And thanks to Chuck, I was just beginning mine.

Thank You, Chuck

By Michele Hall

I was never fortunate enough to be on location at sea with Chuck, yet I have many fond memories of being with him, both here in San Diego and in Maui at Whale Tales.

Chuck is remembered by many, including myself, for his adventurousness and good-naturedness. What I remember most about him are his warm and engaging smile, and his encouraging nature. And that in 1976 he recommended that Howard be hired to join the film crew of the feature film “The Deep” in Australia. Howard was excited about this assignment, and after returning home he talked so enthusiastically about having spent time with Chuck and about the other people he’d met. That job opened doors that Howard nourished, and the ripple effect of that experience changed the course of our lives.

And so now, when I think of Chuck, I think of his never-ending enthusiasm for… well, seemingly for everything. And if pressed to recall a particular memory of Chuck, it would be the way he always greeted me so warmly with a bear hug, making me feel so welcome to the diving community.

Thank you, Chuck, for setting such an example for those of us fortunate to have crossed your path.

Me and Mr. Hollywood

By Marty Snyderman

Chuck was my first boss in the diving industry. He was out of the country When shop manager Lou Fead hired me. I was near the top of a tall ladder cleaning the big glass windows in front of the Diving Locker in Pacific Beach when I met Chuck on the day he returned. He walked by the ladder, looked up, and said, “You must be the new guy. Be careful, those windows are expensive.” Then he just walked away, smiling that wry Chuck Nicklin smile. Right then I knew Chuck was my kind of guy.

Not long after I got hired to work at the San Diego Diving Locker, I caught an elbow playing in a pickup basketball game and got a real beauty of a black eye. The next morning the gang at the shop was riding me about it. I thought it was funny and, perhaps, a sign of acceptance. Chuck was there, and I had gotten to know him a little by that time. While I was being razzed by the gang in the dive shop, it struck me that Chuck seemed a little uncomfortable, as if he thought people were going overboard on me.

At the time, I was renting a rat trap of an apartment in Pacific Beach. I was dead broke in those days. My apartment furnishings consisted of only a mattress, but no box springs I was thoroughly embarrassed about my living situation.

That afternoon, alone in my apartment, I saw Chuck’s blue Porsche pull into the driveway. I didn’t want Chuck to see my apartment with my mattress on the floor and no furniture. My mind was racing. I was very inexperienced as a diver, had never worked in a dive shop before, and the only reason I could think of that Chuck would be coming to my place was to fire me. So, when the doorbell rang, I sure as heck didn’t answer it.

The next day at work, I tried to dodge Chuck, hoping that I would not get the axe. Chuck found me and told me he was sorry I was not home when he came by my apartment the previous afternoon. He told me he had come by to ask if I wanted to go with him to La Jolla Cove to play croquet and cook some burgers. That was Mr. Hollywood, the guy who was making sure the new kid on his staff, the one with the shiner, wasn’t going to be left out.

Decades later, I told Chuck why I hadn’t answered the door that day. He laughed.

And that is one of my favorite Chuck Nicklin stories.

Full Circle

By Marty Snyderman

Considering where Chuck and I were in our lives in 1975 I never would have imagined that some 40 years later I would enjoy the opportunity to share a stage with Chuck as I presented him with the 2015 California Scuba Service Award. But that is exactly what happened. As the Senior Editor of the monthly publication California Diving News it has been my privilege to present the award the past several years.

The California Scuba Service Award was created in 1989 and is awarded to one standout annually at the Long Beach Scuba Show in recognition of the recipient’s long-lasting contributions to the California sport diving community. The list of previous recipient’s reads like a who’s who in the world not only of California diving but in the greater diving community as well with recipients having made huge contributions in diving safety, education, manufacturing, commercial diving and more.

But life being full of unexpected twists and turns, at a Saturday evening function attended by more than 600 people I stood on stage and presented my first boss in the diving business with the 2015 California Scuba Service Award.

When I spoke, I was able to share the story of Chuck moving with his family to California from Massachusetts as a teenager, how he soon fell in love with the ocean and diving by shooting fish and exploring the kelp beds off the coast of San Diego, learned retailing by working at his family’s grocery business, and eventually opened the San Diego Diving Locker and went on to build his highly successful career. I also told the audience how instrumental Chuck had been in helping the San Diego Underwater Photographic Society get established and grow.

As I closed my part of the presentation, I told the audience that like every other guy that worked at the Diving Locker back in the 1970s, and like many of our customers and friends that I, too, said back in those days, “When I grow up, I want to be like Chuck.”

I concluded by saying that now some 40 years later I still do.

Red Sea Revisit

By Howard Rosenstein

I first met in 1977, when he accompanied Dr. Eugenie Clark, David Doubilet and Anne Doubilet when on assignment for National Geographic in the Red Sea (Flashlight Fish of the Red Sea NatGeo November 1978). Genie and the Doubilets had previously used our Red Sea Divers center in Sharm el Sheikh as a base for several Red Sea articles and they were like family.

Chuck with his calm, “California cool” manner, great diving skills and hard work ethic quickly became part of our Red Sea Divers family and would come back to dive with us on many occasions – most notably to film a BBC documentary on our discovery of the Dunraven shipwreck, “Mystery of the Red Sea Wreck.”

He worked on the world’s first IMAX Underwater feature, “Nomads of the Deep” accompanied by son Flip. In the late 1970s Chuck began leading countless dive travel groups through his Diving Locker chain of shops in the San Diego area.

On another assignment for Geographic, again with Genie and the Doubilets, we were using our small skiff, when a rare and unexpected storm picked up out of nowhere. With the small boat heavily laden with camera gear we decided to make a run for it back to the relative calm of Naama bay only a few kilometers to our north.

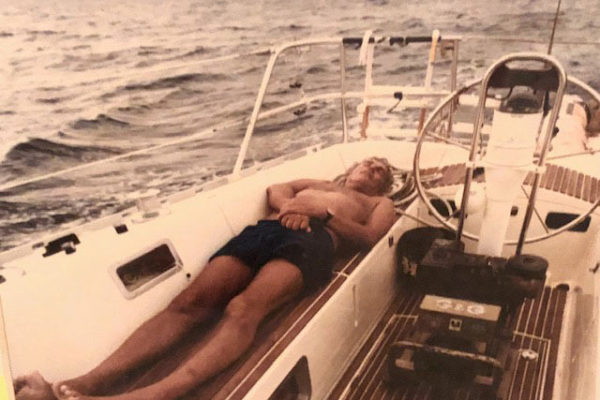

Before heading into the heavy seas outside the bay, I tried my best to lash down all the expensive gear. The boat being very low in the water, I was worried that we might lose something, or maybe worse. I had everyone put on their BCs, fins and mask in hand just in case. The light was fading fast, and as we headed into the strong seas, I kept calling out to the group, Genie, you ok? David, you ok? Anne, you ok? All responded fine, but for some reason, nothing back when I called out to Chuck. I started to worry and pulled out the boat’s torch, to see what was with Chuck. As the light hit the bow section, diving bags, cylinders, photo gear lying lashed all about, I made out the shape of Chuck all curled up and sleeping like a baby.

I just couldn’t believe it. Only later to learn that Chuck this uncanny ability to sleep anywhere, anytime and under the most extreme circumstances. Something he was famous for, with everyone who knew and worked with him.

The one story, that really sticks out in my mind, had more to do with Chuck the man, the friend and not Chuck the diver.

The year was 1977, Chuck had just finished leading his first Diving Locker group to dive with us in Sharm.

We were struggled to keep our pioneering diving operation on track, the challenges were many – wars, terrorism, and extreme conditions wracked the Mideast, trying to operate a quality operation in a very remote location far from many diving markets.

Chuck really wanted to help his Red Sea friends. So, when he returned home after a wonderful group trip. He wrote a letter to Menachem Begin, Prime Minister of Israel. I’ve saved this letter for 45 years. I am sharing it for the first time now.

Thank you, dear friend, for the great adventures and wonderful memories, you were loved by many, you will be missed.

The Challenging Chuck Nicklin

By Al Giddings

The task of writing something considerably more than adequate about Chuck Nicklin’s decades of undersea accomplishments has proven a challenge!

According to Webster’s Dictionary, the word challenge means “demanding all of one’s abilities in a stimulating way.”

Chuck Nicklin’s pioneering years as a premier undersea photographer span more than five decades and include hundreds of historic firsts. I pray what follows carries the full weight of his accomplishments.

Chuck and I met in 1962 on a crowded each in La Jolla, California. Chuck was tall, handsome, with a dynamite smile and vise-like handshake. That day we both carried spear guns and patiently waited for the national spearfishing competition to start. In the early ‘60s we both owned modest underwater cameras but gave little thought to earning a living taking underwater photographs. That would soon change, and photography would become a passion beyond our dreams.

As our friendship matured through the ‘60s, I realized full measure that beyond Chuck’s engaging ways and broad smile was a superb athlete. It became obvious that Chuck was totally at ease in the sea. Equipped with only a mask and swim fins, Chuck could comfortably spear a rock fish in 80 feet of water or take a picture at twice that depth with scuba gear. Few in those early days could match Chuck’s aquatic skills and watermanship; abilities that would serve him in the future in ways beyond his imagination.

By the early ‘70s I was producing documentary films about the wonders of the underwater world. Very often, Chuck and I worked in deep, dangerous open sea conditions where visibility was only a few meters and water temperatures ran into the 40s F. With Chuck onboard, I committed to dicey projects like filming the wreck of the Andrea Doria, lying in 220 feet of water. Chuck was at the top of his game and took on the Doria challenge with a fearless, smart attitude. I rarely worried about him knowing that he instinctively knew when to hold and when to back off.

During those formative years, we worked shoulder to shoulder recording endless firsts for Emmy awarded shows on great white sharks, humpback whales, and lost Japanese warships in Truk Lagoon. One of our more riveting encounters took place in Hawaii while trying to film elusive humpback whales. The day was stunning, the water crystal clear. Less than 100 feet away, a 40-ton mother and newborn calf hung motionless in the water column. My heart pounded as I held my breath and drifted toward the pair, camera rolling. Mother and calf soon filled my frame! At touching distance and with my film roll spent, I eased under the pair as the mother whale slowly guided her newborn forward and away. Red in the face, I exhaled knowing my shot was a stunning detailed first! I was more than thrilled. As I turned toward the boat, Chuck came into view. Somehow, he had skillfully settled into a prime angle and filmed the spectacular encounter with his super wide camera. Months later in a dark editing room, I smiled as I cut the sequence. There was no doubt that my coverage of the whales was riveting. However, Chuck’s take was clearly the stunning super master; an angle that gave spectacular perspective and scale! Chuck’s angle was the selected “money shot.”

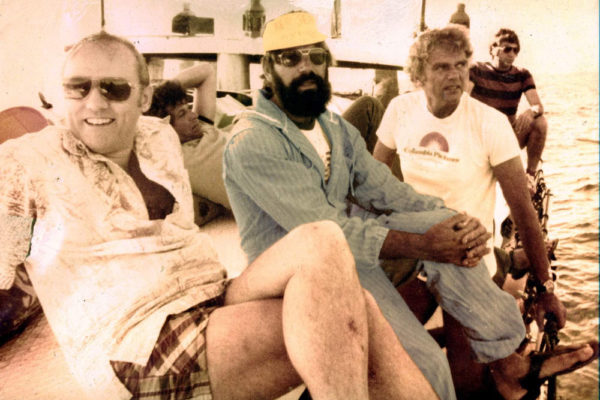

By the late ‘70s, Chuck and I shared the first of many Hollywood Adventures. United Artist funded a movie called “Sharks’ Treasure” staring Cornel Wilde. We got the call. Cornel proved to be a brave actor, so with fingers crossed, Chuck and I and our underwater unit flew to Australia and filmed some very wild shark frenzies and zany shark cage close-ups of Cornel. As they say in Hollywood, “Sharks’ Treasure” ‘didn’t play’ but our wild, open sea shark action registered with Columbia Pictures execs then in the early production stages of one of Peter Benchley’s stories. In 1976, “The Deep”, went through the roof, grossing 130 million for Columbia Pictures. Stan Waterman, Chuck and I were heroes. Chuck’s camera work in the challenging Panavision wide-screen theatrical format was, as always, stunning!

Soon other Hollywood features came our way. In the ‘80s the Bond films here hot. “For Your Eyes Only” had major underwater drama as did “Never Say Never Again” starring Sean Connery and Kim Basinger. Chuck and I, with our crews, had the time of our lives and pay days were especially sweet!

In 1988 I received a call from film director Jim Cameron asking if we could meet and review a major feature he was planning with Fox Pictures. Within weeks we had a deal and “The Abyss” was launched; without a doubt, the most demanding ambitious underwater production ever attempted. My first call was to Chuck followed by calls to dozens of other seasoned vets. Working 91 long nights in an underwater set the size of a football stadium, we burned through 10,460 tanks of air. It was our toughest underwater project ever.

What I’ve written touches only the surface of Chuck’s stellar accomplishments. What we learned together, recorded and shared with the world via our cameras, has carried personal rewards beyond our dreams. Our partnership was a spectacular, thrilling ride; a ride I cherish and will forever be thankful for.