This is the last of three articles on how to identify whales commonly seen off the California coast. Humpbacks were featured last month and grays before that; this month we feature the blue whale (Balaenoptera musculus). All three are baleen whales — Mysticeti. Their cousins the toothed whales, which include sperm whales and orcas, are known as Odontoceti.

Humpbacks and gray whales breach frequently, allowing topside watchers to see nearly their entire bodies. Blue whales rarely breach, however, and those seeking to identify them must rely on blows, flukes, skin color and certain other physical features that can be seen when the whales are swimming on the water’s surface.

Glimpses only hint at their size. According to the American Cetacean Society (ACS) blues can be 100 feet long and weigh 150 tons. Females are slightly larger than males. Considered “the largest animal that ever lived,” adults can be longer than the longest freight train car. Their tongues can weigh as much as an elephant and their hearts, as much as an automobile.

You would expect animals this size to be slow and blues’ cruising speed is a sedate 12 mph though they can reach speeds as fast as 30 mph when need be.

Blue whales’ long, tube or torpedo-shaped bodies are a smooth, metallic blue-gray with light gray blotches. Their skin looks like a tapestry. The undersides of their pectoral fins and flukes may be a slightly lighter color. Although blues do not host nearly as many barnacles as humpbacks and grays, they do have some on the edges of their flukes and, occasionally, on the tips of their pectoral and dorsal fins.

Blue whales reach sexual maturity between the ages of six to ten years. Calves are born every two to three years after a gestation of 11 to 12 months. The babies can be 27 feet long and weigh as much as three tons. They nurse for the first seven to eight months, ingesting 100 gallons of their mother’s milk and gaining about 200 pounds daily. No wonder whale moms need to rest after their babies are born!

The blue whale diet consists mainly of tiny shrimp known as krill, which are strained from the water by bristles on the baleen plates in the whales’ mouths. The water drains out and the krill are eaten. Blues are thought to live 80 to 90 years.

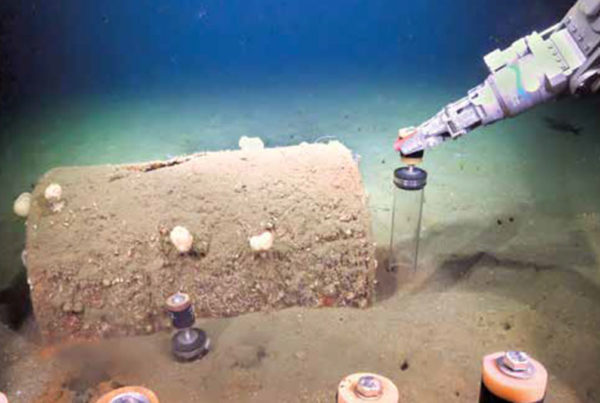

Would you jump into the water with blue whales? I have the greatest admiration for those who do so now — many of them photographers — but even more for those who did this in the early years when no one knew how these behemoths would react to humans who showed up in their habitat. Jim Hudnall is credited with being the first to film a blue underwater in the 1980s and Howard Hall was the first to film blue whale feeding behavior underwater (1988).

At least those venturing into the water have never had to worry about becoming blue whale food. I found the following tidbit on the Whale Facts website: “…the blue whale can only consume small prey because its esophagus is too small to consume larger sources of food and it is unable to chew its food and break it down into smaller pieces … the blue whale’s esophagus is so small that it would not be able to swallow an adult human.”

Like the other big whales, blues are very slowly recovering from being hunted almost to extinction. For a while their size and speed saved them. They were simply too big to be hunted from open boats. Also, their carcasses sank. But once technology solved those problems, the slaughter began in earnest. Before they were finally protected by the 1966 International Whaling Commission moratorium, which banned the hunting of all whales, and the 1972 Marine Mammal Protection Law, it is estimated that 99 percent of the population had been eliminated. There has been only a minor uptick in their numbers since then. On The Endangered Species list they are shown as, “Endangered, population increasing.”

Blues are found in all oceans worldwide. Prior to being hunted there were an estimated 350,000. Today it is believed 5,000 to 10,000 live in the Southern Hemisphere and 3,000 to 4,000 in the Northern Hemisphere. There is also a blue whale subspecies, the so-called pygmy blue whale, which is found in the Indian Ocean and the South Pacific. It can be 70 to 80 feet long.

Researchers have detected blue whale calls off our coast between June and January. The whales are known to migrate to Southern California in the late spring from the coast of Mexico and even as far south as Costa Rica. However, no one knows where they go when they leave our waters in early winter and where they breed is a mystery.

Blue Whale Stats:

Phylum: Chordata

Subphylum: Vertebrata

Superclass: Gnathostomata

Class: Mammalia

Order: Cetartiodactyla

Infraorder: Cetacea

Superfamily: Mysticeti

Family: Balaenopteridae

Genus/Species: Balaenoptera musculus

Special thanks to the American Cetacean Society, whose website was the main source of information for this article. Also vital in its preparation were Genny and Shane Anderson.

This is the last Marine Life column Bonnie Cardone submitted before her death. We’ll always be grateful to her contributions to CDN. Next month we’ll debut two new columns in this space.