Make a dive in a southern California kelp forest and it is highly likely that a bright reddish-orange damselfish called a garibaldi will soon catch your eye. Sometimes these pugnacious fish boldly swim right up to their human counterparts as if wanting to be noticed. At other times, they couldn’t seem to care less about anything other than their daily affairs. Either way, no matter how many times you encounter garibaldis, it is hard to take your eyes off these standouts.

One of the first things I learned when I moved to California in 1975 was that the garibaldi (Hypsypops rubicundus) was California’s official state fish. It was something I heard over and over again. The problem was that although widely believed, this information was not true. To some degree there has been and still is some confusion about the status of this iconic fish.

Today, the garibaldi is officially recognized as California’s state marine fish. The golden trout (Salmo aguabonita, also written as Salmo agua-bonita) is designated as the official state fish.

In this article I will share the story of how the garibaldi became designated as our state marine fish and reveal many fascinating aspects of the natural history of this beloved species.

The Garibaldi’s Path to Becoming California’s State Marine Fish

Because of the garibaldi’s beauty, popularity, limited stock, and the realization that the fish was not widely sought after as a food source, in 1971 the California Department of Fish and Game recommended to the State Legislature that the garibaldi be fully protected. This protection would mean garibaldi could not be taken for sport or commercial reasons. However, despite what many people believed, this recommendation was not acted upon.

For the next 22 years, commercial fish collectors targeted garibaldi because of its strong popularity with hobbyists and the fact that these damselfish are relatively easy to catch. In addition, a small number of spearfishermen were known to pursue garibaldi. Sad, but true.

In 1993, legislation was passed that was intended to protect garibaldi from being over harvested. Live captures were prohibited from February 1st through October 31st. Even so it was widely believed that commercial collectors continued to greatly reduce the garibaldi population in many areas, and in 1994 Assembly Bill No. 77 was introduced with the intent of putting a collecting moratorium in place so the state’s garibaldi population would recover. The bill was enthusiastically backed by a grassroots campaign led by Jean-Michael Cousteau’s Ocean Futures Society.

Not surprisingly, however, amendments slowed the bill’s passage. Finally, in September of 1995 the bill was signed into law by then Governor Pete Wilson on October 16, 1995. The bill contained a section that designated the garibaldi as California’s official state marine fish. As a result, the garibaldi is protected. Today, removing a garibaldi from the waters off California requires a special permit, not just a valid fishing license.

The brilliantly colored reddish-orange bodies of the juveniles are covered with iridescent blue spots.

A Darling Damsel

The garibaldi is a member of the damselfish family, Pomacentridae, a grouping that includes approximately 392 species described in 30 genera. Attaining a maximum length of approximately 15 inches (38 cm), the garibaldi, Hypsypops rubicundus, is believed to be the largest member of its family.

Occurring in tropical and temperate seas around the world, damselfishes tend to inhabit relatively shallow water, as is the case with the garibaldi, a species that prefers to inhabit rocky reef communities in the top 100 feet (30 m) of water. However, there are family exceptions with some damselfishes being present in areas as deep as 1,250 feet (381 m). While known in all tropical seas, the greatest numbers of damselfishes inhabit the waters of the Indo-Pacific.

Damselfishes are commonly described by divers as being feisty, pugnacious and irascible. Many species are known for their vigorous defense of their territory and their willingness to physically confront intruders—including divers—many times their size. Inhabiting reef communities, the individuals of most damselfishes species typically remain close to the sea floor where they feed on bottom dwelling organisms such as algae, myriad invertebrates, and fish eggs. However, those species described in the genus Chromis feed on planktonic organisms in mid-water.

Although there are numerous exceptions, many damselfishes are characterized by their brilliant coloration, a characteristic that is especially evident in juveniles. While it is not a trait that stands out to laymen, a single nostril on each side of their snout is another feature that characterizes damselfishes. Most other species of bony fishes possess four nostril openings with a pair being located on each side of the head. Most damselfishes have bodies that are flattened from side to side, and generally disc-like. While bearing some resemblance to angelfishes and butterflyfishes, many damselfishes are easy to distinguish by noting that they look like “pug-nosed perches.” However, the species described in the genus Chromis are an exception. These damselfishes have longer bodies and distinctly forked tails.

The 104 species of damselfishes described in the genus Abudefduf are commonly referred to as types of sergeants, examples being the sergeant major and Indo-Pacific sergeant. Various species of sergeants occur in tropical seas throughout the world and often grace the photographs of postcards from exotic locales. These fishes routinely gather in loose aggregations in coral reef communities as well as close to debris and boat docks. In many respects, the behaviors exhibited by sergeant majors are like those exhibited by the garibaldi.

An adult garibaldi poses for the camera.

‘Baldi Basics

The garibaldi occurs in reef communities and kelp forests ranging from central California’s Monterey Bay southward to Magdalena Bay, a well-known birthing ground of California gray whales located roughly halfway down the Pacific coast of Mexico’s Baja peninsula. Garibaldis are also present at Guadalupe Island off the northern portion of central Baja, a destination widely known to divers as a site to see great white sharks. Within California waters, divers and snorkelers are more likely to encounter garibaldi the further south we explore, and it is quite common for beachgoers to spot their brilliant reddish-orange bodies from the shoreline as garibaldi dart through the shallow waters of rocky reefs and tide pools that are close to nearby kelp beds.

The common name, garibaldi, is believed to be a reference to the Italian military and a prominent political and military figure of the mid-1800s, Giuseppe Garibaldi, whose followers often showed their allegiance by wearing a bright reddish-orange shirt.

As is the case with so many species of damselfishes, garibaldi are highly territorial. Adult males vigorously defend a staked-out patch of reef on the rocky sea floor. This section of reef typically covers several square yards, and the males do what they can to keep other garibaldi as well as other intruders out of their domain.

There is no question regarding the fact that adults are very particular about the boundaries of their territories. Neighboring garibaldi may graze peacefully within a few inches of each other together at the edges of their territories. But if neighbors come too close, they will face each other head-to-head and rapidly wave their tail fins in an effort to establish clear boundaries. Competing males also produce popping sounds made by drumming their swim bladder. Easily heard by nearby divers, these low frequency sounds are used to discourage intruders.

The brilliantly colored reddish-orange bodies of the juveniles are covered with iridescent blue spots. Though most fish lose the blue spots as they mature, some specimens retain a blue color along the border of their fins. The brilliant blue spots on juveniles serve to advertise that these fish are juveniles, thus preventing attacks by the territorial adults.

Garibaldi mostly feed on a variety of sponges, worms, and crabs. As is the case with many fishes, size correlates with age in garibaldi. A 6-inch-long garibaldi is estimated to be about three years old while a 12-inch-long fish is thought to be at least ten years old. A length of 15 inches is about as big as garibaldi get.

Nesting, Courtship and Reproduction

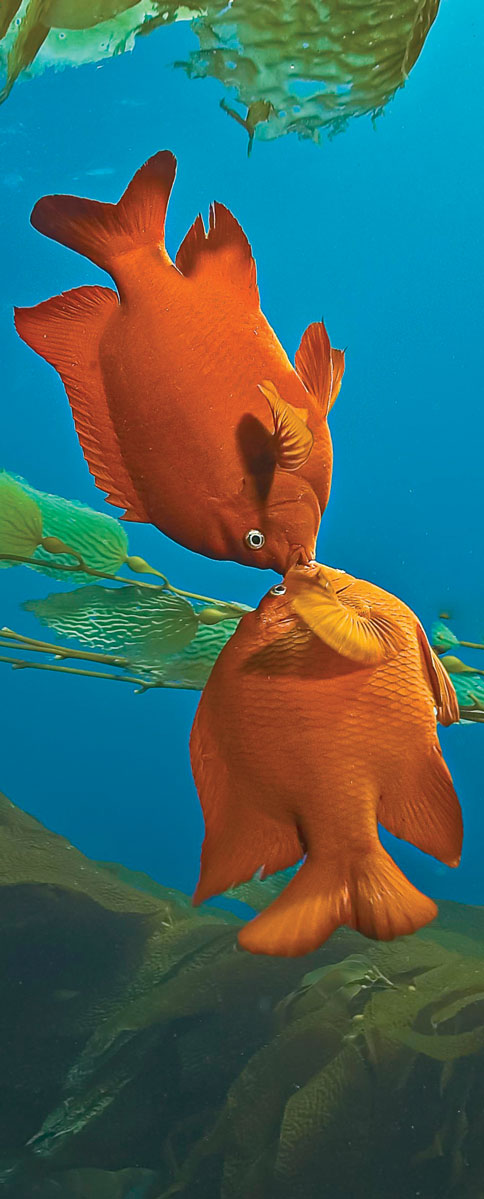

A pair of adult garibaldi in a physical confrontation and a display of territoriality.

Garibaldis attain sexual maturity when they are five to six years old and reach a length 8 to 9 inches (20.3 to 22.8 cm). For the adults, love is in the water in the spring and early summer. When a male reaches adulthood, he will select a patch of reef that is to his liking and not inhabited by another male, although other males often make their homes in immediately adjacent patches of the same reef. The chosen site is the general area where the male will live out the remainder of his life.

In preparation for and during its breeding season that extends from March to July, a mature male will build and maintains a nest by cultivating a patch of red algae that is several feet (1 foot = .3 m) in diameter. Nests are typically made in a sheltered cranny on a smooth portion of a vertical rock. The males clear away all growth except for three species of red algae. They also get rid of debris, sea stars, sea urchins and other intruders.

Males keep the algae in their nests trimmed to a height of one to two inches by nipping at the tops of the algae. Once the males have cultivated the algae to their liking, they are faced with the age-old problem of attracting a mate. When a potential mate enters a male’s territory, he will try to entice her to lay her eggs in his nest by making loud clicking noises and by making himself obvious as he rises away from the nest and zips around in a series of elaborate patterns to make himself seen as he “struts his stuff.”

Mature males try to woo females and encourage them to lay their eggs in their nests. The males work in feverish fashion to trim the algae to a length of roughly one inch, as each attempts to make his nest “the most desirable place” for the highly selective females to lay their eggs. In addition, the males tirelessly groom and defend their nests against competing males and other intruders.

Once the males have cultivated the algae to their liking, they are faced with the challenge of attracting a mate. When a potential mate enters a male’s territory, the male will try to entice her to lay her eggs in his nest by making himself obvious as he rises away from the nest and “struts his stuff” by swimming in a series of elaborate patterns while also making loud clicking noises by grinding teeth in his throat (pharyngeal teeth).

Females are extremely picky when it comes to choosing a mate. Laying between 15,000 and 18,000 eggs, females prefer to deposit their eggs into large nests that contain some eggs that have already been placed by other females. If the male is dashing enough and the nest suits her, the female will deposit her eggs, and then she will swim away. If she lingers, the male will quickly chase her away to prevent her from eating some of her own eggs. The chosen male then fertilizes the eggs and tends to them until they hatch some two to three weeks later.

Interestingly, several females are routinely persuaded by a single male to lay their eggs in the same nest during the same season. The age of those eggs is a factor in the females’ decision making as they prefer to place their eggs next to more recently deposited yellowish eggs.

In addition, the same female often deposits her eggs in the nests of more than one male. However, females often avoid a nest that appears to be filled with eggs. It is also believed that males sometimes eat some older, already fertilized eggs to vacate space in a gamble that they might gain even more eggs from a variety of females. Conversely, females often avoid nests that are not partially filled with eggs, but willingly deposit their eggs in nests filled with eggs from as many as twenty other females. In short, a courting male must work very hard to entice his first partner to lay her eggs in his nest, but after that he sometimes has several females ready to lay their eggs in his nest in an assembly line like manner.

After two to three weeks—a period that is thought to vary with water temperature—the fertilized eggs hatch. The hatchlings usually emerge within the two-hours long period following sunset. The larvae are then dispersed by the currents with the planktonic population. In late summer and fall, those fish that survive settle to the rocky reefs. Garibaldis are known to live as long as 17 years, but 12 years or less is more typical.

THE BIG WOO

When it comes to being a male that is an attractive mate, in garibaldi size is highly important. In addition to performing an elaborate “courtship dance,” males that are wooing females also “thump” their swim bladder to produce low frequency sounds that are easily heard by female garibaldi as well as divers who know what to listen for. The physically larger a male is, the lower the frequency of the emitted sounds. The lower the frequency, the better chance a male has of sealing the deal with the female of his dreams.

Strip away the fantasy while looking at things from a scientific perspective, and it makes perfect sense that large size in a male is highly attractive to females. Larger size is an indicator of physical prowess, good health, and desirable genes, factors that maximize the chances of the female passing her genes along into future generations.